Access to broadband internet is fast becoming a predictor of whether you are on the “have” or “have not” side of the American wealth divide. If you can’t access high-speed internet regularly and don’t know how to take advantage of it, you probably won’t do as well in school, won’t know about good available jobs and won’t be able to get those jobs if you did.

As documented in a white paper on rural persistent poverty published by NeighborWorks, achievement of higher education, employment and broadband access often go hand in hand. [Note: the Federal Communications Commission defines broadband as both a download speed of at least 25 megabits per second (mbps) and a minimum upload speed of 3 mbps.] Sixty-70 percent of jobs are posted online—80 percent for those with bachelor’s degrees or higher. Likewise, nearly 8 in 10 middle-skill jobs in today’s workforce require digital skills, representing 32 percent of all labor market demand in the nation. In fact, in the past decade, digitally intensive middle-skills jobs have grown more than twice as fast as those that are not, and pay wages an average of 18 percent higher.

Many people don’t find that alarming. A March Pew survey found that fewer than half of adults (44 percent) think the government should provide subsidies to help lower-income Americans pay for high-speed internet at home. That is in part because 54 percent think high-speed home internet service is affordable for nearly every household. However, that is clearly not the case. In addition, there are many other reasons beyond cost for the growing digital divide.

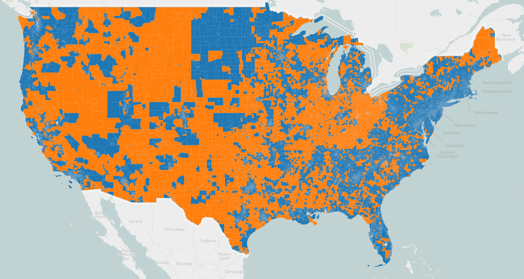

The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas reported in 2016 that “roughly one-third (31.4 percent) of households with incomes below $50,000 and with children ages 6-17 do not have a high-speed internet connection at home. This low-income group makes up about 40 percent of all families with school-age children in the United States. Rural areas also are much less likely to have broadband access than suburban or urban communities: According to data collected by NeighborWorks America, 45 percent of rural tracts don’t qualify as having broadband internet, compared to 17 percent for suburban and 11 percent for urban areas.

Increasingly, nonprofits like NeighborWorks America members are partnering with others to close this gap, both to equip residents in their properties with the tools they need to support their families and as an often-overlooked component of comprehensive community development. Here a few examples to offer a flavor of just what can be accomplished, how and the lessons learned:

Taking a portfolio-wide approach: Eden Housing

Eden Housing in rural Hayward, California, has long been ahead of the curve, offering education in digital literacy via programs such as its “Digital Connectors” youth program and “Generation Exchange”—in which young people teach computer skills to seniors. However, it now realizes that’s not enough. “We originally focused on educating and inspiring our residents to adopt broadband, but then we learned that for many of our residents, the monthly fees for access cause a severe hardship to the family,” explains Jennifer Reed, director of fund development and public relations for Eden. “So now, we are expanding to a portfolio-wide approach to provide access as well. We call it Communities Wired!”

“We originally focused on educating and inspiring our residents to adopt broadband, but then we learned that for many of our residents, the monthly fees for access cause a severe hardship to the family,” explains Jennifer Reed, director of fund development and public relations for Eden. “So now, we are expanding to a portfolio-wide approach to provide access as well. We call it Communities Wired!”Using a grant from the California Emerging Technology Fund, Eden surveyed current residential adoption rates across its properties, identified residents' desires and needs, forged alliances with partners, and created a digital literacy toolkit. With additional funding from the California Public Utilities Commission, it has set out to achieve its goal of providing free or very low-cost internet access to all of its residents within five years (ideally in each unit, in a community space at the minimum).

To date, free broadband has been extended across 11 of the properties. And it’s being used! At one of the senior-housing sites, data show that nearly 100 percent of the residents have accessed the internet compared to an average of 40 percent in other developments for seniors where free services is not yet available.

Finding creative ways to staff a digital focus: Charlotte-Mecklenburg Housing Partnership

In 2004, the National Bureau of Economic Research published a paper titled, “Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States.” Charlotte, North Carolina, says Kim Graham, CMHP’s senior vice president for outreach and fund development, was “dead last” of the 50 communities studied when it came to children born into poverty being able to transition out by adulthood.The city of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County took that finding seriously and convened a task force to identify the root causes. CMHP partnered with leaders of the task force to organize the first of several town hall meetings to solicit resident input. Access to technology—both the internet and the devices needed to access it—emerged as one of the factors contributing to the lack of upward mobility.

“We were fortunate and blessed to be able to retain a PhD candidate in urban analysis who had previous experience in both teaching and research,” says Graham. “Plus, she had a track record of outreach into Charlotte’s more challenged communities.”

Although the grant is only for one year, a “train-the-trainer” component is designed to produce graduates who can keep up the work once the fellowship period is complete. The curriculum was adapted from several good modules available online, such as the ones from the Northstar Digital Literacy Project. However, training in how to use computers and the internet is not sufficient. What’s the point of knowledge if you don’t have a tablet or laptop? Or Wi-Fi?

In addition to funding the fellow, NTEN also gave CMHP $5,000, which it matched. With the additional help of E2D (End the Digital Divide) and the Kramden Institute—both of which serve North Carolina specifically—CMHP was able to give refurbished tablets to participants in its related programs. CMHP also plans to purchase wifi “hot spot” devices to loan out to residents in its newest affordable-rental apartment community. The public library already had established a tradition of such loans, but only for students.

What have been the lessons learned?

“Our biggest discovery was that most of the people who signed up for our classes have been adults, including seniors,” says Cache Owens, CMHP's digial inclusion fellow. “So make sure you tailor what you teach to who’s in your classroom. Know what they are there to learn.”

For example, among seniors, online safety (such as how to protect against viruses), Facebook (to talk to grandchildren) and getting the most out of smartphones are among the most popular topics.

Leveraging the internet to revitalize a downtown: Neighborhood Development Services

In Ravenna, Ohio, NDS is on a mission to revitalize the downtown, including a movie theater, a brewery—and public Wi-Fi.“The former city council president came up with the idea that public wifi, instead of a patchwork of private options, would help attract customers to the downtown,” says Kate DeAngelis, marketing and community relations director for NDS. “We decided to help make that happen.”

NDS obtained a two-year, $30,000 placemaking grant from Ohio Capital Corp. and is using it for the necessary fiber-optic cables, rooftop antennas, cloud subscription, etc. It is expected to be up and running by the summer.

The internet signal will "ping" off of phones, giving business owners an idea of how many people with smart phones have passed their doors, how many have used the Wi-Fi and how many came in to their business, information that can be used for marketing purposes. The program includes a "splash page," through which users agree to terms of service and provide an opportunity to advertise local businesses.

When the grant period is up, the city has committed to continuing the service—perhaps by offering it at a rate that is less expensive than private competitors to other local businesses.

Packaging devices with education: Affordable Housing Alliance

New Jersey’s AHA intentionally focuses on seniors in its Successful Aging and Technology (SAT) program. The program was originally run in a more limited fashion by the local Social Community Activities Network (SCAN). However, its government grant ran out and AHA stepped in with its Community Services Block Grant dollars.SCAN’s team of technology coaches—often peer instructors, such as retired employees from technology companies—offers a 13-week course on how to use a tablet, access email, surf the web, etc. Participants who qualify as low-income are given a free tablet with a SIM card installed by a local provider. AHA pays for the internet service for a year; at that time they have the skills and are expected to find a way to continue it on their own (such as via the senior discount offered by the local provider) or to use public facilities.

“For example, we show the seniors how to use the web to save money by ordering medicine online and to Skype or share photos via Instagram with their grandkids,” says AHA’s CAP director, Peter Boynton. “A lot of the seniors who participate do so because they are alone at home and bored. So another side benefit is the building of a social network. To practice, they have to email each other, and then they make new friends.”

Classes are held in natural gathering places such as senior centers and residential community rooms, due to the lack of transportation—which Boynton says is a big barrier.

Tackling the divide with a regional focus: Coastal Enterprises, Inc.

Today, what began as meetings of eight to 10 people has grown to include more than 200, due to the recognition of the importance of the issue. Dickstein is co-chair of the coalition and the state’s small business advocate staffs it. GWI built its website. And more than 10 bills are currently being discussed in the legislature to put in place what’s needed to change Maine’s 49th-place ranking among American states in the quality of its broadband services.

What is Dickstein’s advice for others? “The coalition needs a backbone and people who can stay on top of it. A dedicated leader will keep the coalition focused.”