Julie Saylor, library associate II and a tour guide for the exhibit Undesign the Redline, looked at the group gathered around her at Baltimore's Enoch Pratt Free Library and asked her opening question: "How many of you know what redlining is?"

Hands shot up — lots of hands.

The group comprised staff members from NeighborWorks America where the mission is creating opportunities for affordable housing and strong communities. Redlining could be considered the antithesis to that mission. It created racial and ethnic inequities and wealth gaps that continue long after the Fair Housing Act banned the discriminatory, color-coded maps that ranked neighborhoods according to the people who lived in them. The maps were a guide for withholding loans from those whose zone and skin were deemed to be the wrong color.

The group comprised staff members from NeighborWorks America where the mission is creating opportunities for affordable housing and strong communities. Redlining could be considered the antithesis to that mission. It created racial and ethnic inequities and wealth gaps that continue long after the Fair Housing Act banned the discriminatory, color-coded maps that ranked neighborhoods according to the people who lived in them. The maps were a guide for withholding loans from those whose zone and skin were deemed to be the wrong color.

The exhibit, by design studio Designing the We, featured cultural, racial and political history, headlines and maps from the first half of the 20th century. But the timeline, which began with the 1800s, moved forward. The group's focus moved forward, too, during a discussion organized by members of NeighborWorks America's race, equity, diversity and inclusion (REDI) team and its public policy and legislative affairs division.

"We want to get a better understanding of why things are the way they are and how these things impact our work," explained Don Trahan Jr., NeighborWorks America's REDI director.

Along with representatives from two Baltimore-based network organizations, staff discussed schools, immigration and disinvestment. They talked about "block busting" — convincing homeowners to sell at a loss because people of a minority religion or race, often black, were moving in. And they discussed what Baltimore might have looked like if redlining hadn't taken place.

"Less sprawl and slower suburbanization," said David Sann, director of housing development for St. Ambrose Housing Aid Center. "The perception of many in the white community was that when blacks moved in, the neighborhood went down. I can't help but think how much of that stereotype was exacerbated by the devastating impacts of redlining."

Saylor addressed climate change and "heat islands" — urban areas that grow hotter than the areas around them, in part due to little vegetation or green space. "They tend to follow areas where the redlining was," she said. "So, the people in historically redlined areas will have that to deal with."

The climate component was new to Tayna Frett, senior vice president of administrative services and facilities for NeighborWorks. She said she's glad the exhibit, which closed in Baltimoreon Jan. 31, was available to the larger community. "I grew up in New York around and in neighborhoods that were a direct result of redlining," she said. "It's good for everyone to be aware of what redlining actually is. Most people just see the results."

Baylee Childress, senior specialist for NeighborWorks' national homeownership programs and lending, said the exhibit was a great reminder of why we do what we do. She added that she has enormous respect for our network organizations. "They're fighting against decades of institutional racism and disenfranchisement that still plague our nation's communities today."

While the exhibit at Enoch Pratt featured Baltimore, it highlights other cities — Los Angeles, New York, Boston — as it travels around the United States.

Unique city, unique issues

Baltimore has unique issues when it comes to affordable housing. As the community with the most row houses in the United States — an estimated 80 percent of housing stock — renovations can be difficult and costly. You won't see teardowns the way you will in other areas, said Dan Ellis, executive director of Neighborhood Housing Services of Baltimore, because "everything is attached." Instead, you'll see a sound home next to a decaying one. Baltimore also has 16,000 vacant houses and Ellis estimated thousands more are empty but not classified as "vacant" by the city. Because of this, lower-cost homes (in comparison to other urban areas) are available. But the stock isn't in good shape, Ellis said.He said the question we should ask about redlining is not what happened. "The question is what do we do about it?"

Housing is a big part of the answer.

Housing is a big part of the answer.Sann said affordable rentals are especially needed in Baltimore. That's just one focus for St. Ambrose, which formed in the 1960s, picketing against banks with discriminatory loan practices. Sann said many of the properties the organization develops for rent or sale are not located in the red areas of the maps from the 1930s, but in what are now referred to as the "middle communities." Some of the neighborhoods were still farms and forest in 1937.

Those areas have strengths and weaknesses, added Gerard Joab, executive director of St. Ambrose. "They could go up or they could go down." The goal is to provide the support that helps bring them up.

"The effects of redlining have not gone away," Joab said. "We're still dealing with it, so that's part of the challenge."

The fallout can be seen in a persistent wealth gap, said Sann. It can be seen in distressed neighborhoods and empty commercial corridors.

St. Ambrose's neighborhood partners in the Belair-Edison community are working on mixed-use housing to bring businesses back to neighborhoods that need them, including pop-up commercial spaces.

St. Ambrose is also working with seniors on a number of initiatives, making sure they have home improvements, titles to their homes and the ability to pass their homes on to a family member if they choose, Joab said. His hope is that by providing resources, seniors will be able to pass on their assets to family members who will be involved in the communities and stay there, "thus preserving inter-generational wealth and preserving an affordable home, particularly if the neighborhood is being gentrified." Homesharing is another option to help seniors age in place by matching those who want to rent a room with people who might be seeking one.

Being able to stay in a community is key, especially in a city like Baltimore, where the population has decreased by well over 300,000 since its peak of 949,700 in 1950.

"As Baltimore changes over the next 20 years, how do we do it in a way to make sure the residents of Baltimore are able to remain residents of Baltimore and we don't push them out to the surrounding counties?" Ellis asked. "The more folks we can move to home ownership, the more folks will be protected as a neighborhood improves."

The way to do that, of course, is the $300,000 question.

Loans play a huge part, said Ellis, whose agency offers Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) loans and financial counseling. Ninety percent of loans in the United States end up being bought by a government entity, he said. "If you want to change access to home ownership then change the qualifications of what we're going to buy, what we're going to lend, who we're going to lend to," he said. "Broaden that to include people who were impacted and be willing to take the risk associated with that."

Nonprofits also have a role in moving these communities forward. Ellis highlighted three important activities:

Nonprofits also have a role in moving these communities forward. Ellis highlighted three important activities:

- Invest in people: Make sure those making decisions reflect the makeup of the community. Use an equity lens when viewing programs and the work we do.

- Invest in place: Make sure we're actively investing in places that were disinvested.

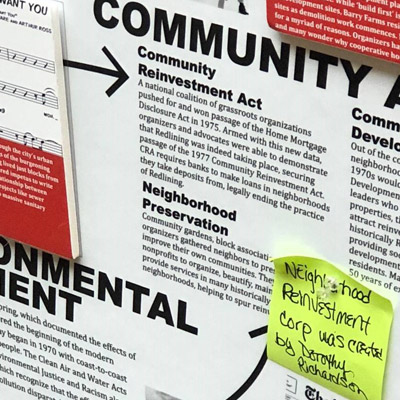

- Reinvest. That's the word Ellis wrote on the card he added with a pushpin to the interactive exhibit. "It's not cheap," he said. "But it's important."

Joab says that while he doesn't expect Baltimore's population to return to what it was at its peak, he does expect it to grow. He looks at Pittsburgh, another industrial city, as an example.

"I'm from here," Joab said of Baltimore. "I'm optimistic. It's a daunting task, but it's possible for our neighborhoods to come back."

Further reading

- David Sann, director of housing development at St. Ambrose, recommends "Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City" by Antero Pietila.

- Undesign the Redline continues to tour.