Opioids are currently the main driver of drug overdose deaths in the nation. In 2017, Health and Human Services declared a public health emergency, and launched its five-point Opioid Strategy. At the top of the list is the need for improved access to addiction prevention, treatment and recovery services.

In Vermont and Kentucky, two NeighborWorks organizations have answered the call to improve access to recovery services, with a particular focus on serving rural areas.

Vermont

"Rural states definitely get the short end of the stick when it comes to the opioid crisis," says Eileen Peltier, Executive Director of Downstreet Housing & Community Development in Barre, Vermont. Vermont is designated as a rural state.Downstreet participates on Vermont's Opioid Coordination Council, which was created by Gov. Phil Scott in 2017. To understand the scope of the problem and to find relevant gaps in housing services, Downstreet commissioned a study, which was prepared by Development Cycles.

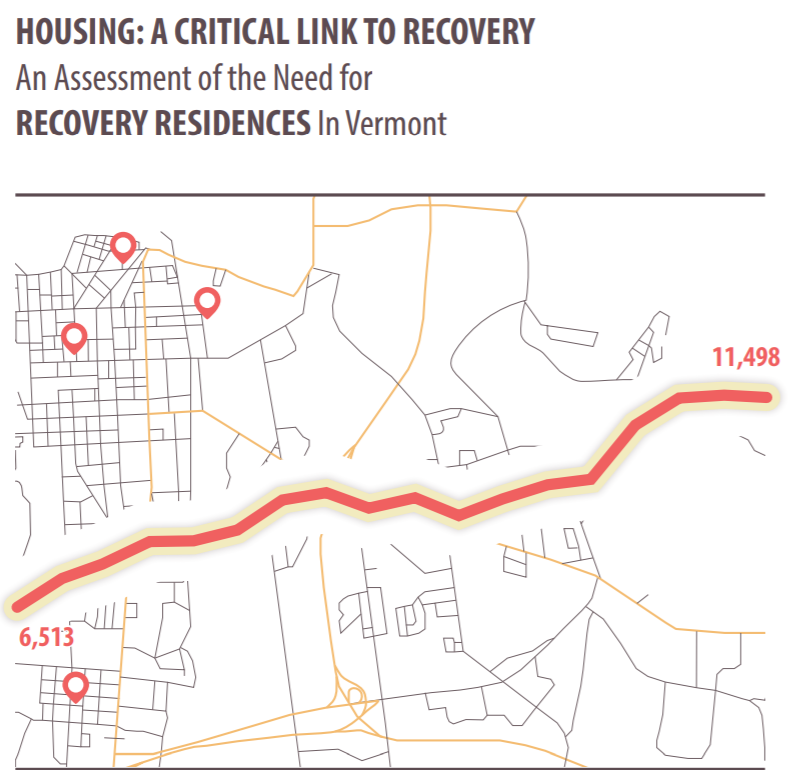

"Housing: A Critical Link to Recovery" revealed that the number of individuals in treatment for opioid use disorder is on the rise in Vermont. In 2000, 399 individuals in Vermont were in treatment for use of heroin or other opioids. By 2017, the number had risen by 1,500 percent to 6,545 individuals.

"Housing: A Critical Link to Recovery" revealed that the number of individuals in treatment for opioid use disorder is on the rise in Vermont. In 2000, 399 individuals in Vermont were in treatment for use of heroin or other opioids. By 2017, the number had risen by 1,500 percent to 6,545 individuals. For an individual who has taken the first step of seeking treatment for opioid use disorder (or any type of substance use disorder) the next critical step in the process may be to live in a recovery residence. This housing model is designed to offer a community of support and should be located close to a treatment facility. Residents may also have access to employment support and job training programs as well.

In Vermont, recovery residences are in short supply. Downstreet's study reveals that in 2017, roughly 1,200 individuals who entered treatment for a substance use disorder would have benefitted from access to a recovery residence, but across the state only 212 beds were available.

As part of the effort to develop a statewide solution, Downstreet is leading a collaborative initiative to develop 12 new recovery residences by the end of 2020. A new recovery residence was opened in St. Johnsbury for men earlier this year. In July, a recovery residence was opened in Morrisville for women. Three additional residences are actively in the funding stage, says Downstreet's Peltier.

To provide resources for communities around the state to replicate the model, Downstreet created a developer's toolkit. It also formed the nonprofit, the Vermont Alliance of Recovery Residences (VTARR), which is an affiliate of the National Alliance for Recovery Residences (NARR). As such, VTARR can certify recovery residences in the state.

For developers interested in moving into this space, Peltier offers some advice: start with a listening tour where you can learn from the service providers already working on issues related to recovery. Next, read the available research to understand the scope of the problem, and find out what local or state initiatives have been put into place. Then, introduce yourself as a potential partner in developing recovery housing or providing access more broadly for people coming out of treatment.

"Not everyone wants to or needs to be in a sober living environment, but they all need housing, and we know that there will be a very high percentage of people who could live in our [affordable] housing," says Peltier.

Kentucky

Fahe administers the Kentucky Access to Recovery program, which is funded by the state's Cabinet for Health and Family Services. The program serves 15 counties from three hub locations and provides gap funding for individuals in recovery that can be used for basic needs support, medical care, child care, and housing for up to a six-month period.The need for additional recovery housing is immense. "Not everybody needs medical or dental care, but almost everybody needs housing. We are not only struggling with trying to find housing, period, but also with trying to find certified, quality, recovery housing," says Matt Coburn, Fahe's Senior Vice President of Strategic Programs.

To increase the supply of recovery residences across the state, especially in smaller communities, Fahe has connected its members to grant funding, as well as helped them to access real-estate owned foreclosed properties that might be suitable for development. This initiative will "help them expand their portfolios, meet the needs of the community, and get involved in a very important crisis that is occurring right in their backyard," says Coburn.

Three of Fahe's member organizations recently developed new recovery residence projects: COAP in Harlan, Frontier Housing in Morehead and Kentucky River Community Care in Hazard.

Additionally, Coburn notes that Kentucky is moving towards making the certification of recovery housing by NARR a statewide priority. To assist its members, Fahe is helping them prepare for the certification process.

For Fahe, this is new territory they are navigating, but the organization remains committed to its central focus of providing affordable housing services.

"I think that we're teetering on new ground, but we're using our same foundation, same knowledge base, and our same way that we have always done things to make sure that we can be successful," says Coburn.