The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service defines counties as persistently poor if 20 percent or more of the population has lived in poverty for the previous 30 years. Think about that. Most of that poverty is intergenerational—passed from one family to another for decades. What if you came from a family in that 20 percent, and you were born into a hopelessness so pervasive and persistent it is tangible, something you can almost touch in the air around you?

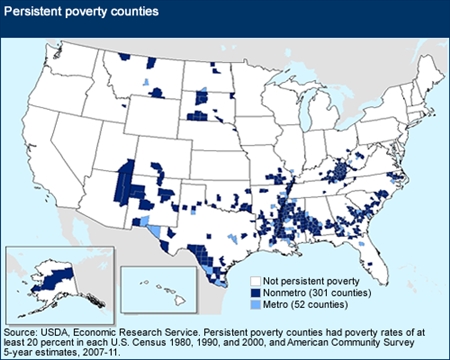

There are currently 353 persistently poor counties in the United States where one in five residents live that reality. Eighty-five percent of those counties are rural. And that’s why NeighborWorks is convening a national forum April 20 in Memphis, titled “Hope in the Delta–Turning the Tide on Persistent Rural Poverty.” What is it that makes poverty so persistent, despite numerous attempts to tackle it since Lyndon Johnson announced his War on Poverty in 1964? What initiatives have been shown to be effective, if they could just be replicated and scaled up? What lessons have the practitioners in this space learned that could provide a blueprint for a path forward? These are among the questions that will be explored at the forum.

To get the “creative juices” flowing in advance, NeighborWorks asked four leading regional- and community-level professionals—leaders of organizations that serve the hardest-hit rural areas in the country—to share their expertise and perspectives in a white paper in advance of the convening.

The entire paper is worth reading, whether or not you attend the forum. (If you’re not, you can register to listen to the two primary panels via a free webcast.) To whet your appetite, I’ve summarized here some of the main observations and recommendations. But first, a bit of an explanation about the authors—the heads of four organizations that serve areas of the country that are unique in their challenges and opportunities, but share some common threads.

- Nick Mitchell-Bennett, executive director of the Community Development Corp. of Brownsville, Texas, speaks for the “colonias”— communities in Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas within 150 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border.

- Jim King, CEO of Fahe, represents the Appalachia region, primarily in portions of Kentucky, Tennessee, West Virginia, Virginia, Alabama and Maryland.

- Bill Bynum, CEO of Hope Enterprise/Hope Credit Union, writes about the Mississippi Delta, known recently for its hurricanes, floods and oil spills.

- Chyrstel Cornelius, executive director of Oweesta, an intermediary for CDFIs serving Native communities, primarily in the Plains and Southwest.

So, why is persistent poverty higher in rural areas? There is no single answer. Among the factors are population loss/lack of density, lack of infrastructure such as transportation, absence of services, a history of natural-resource extraction without adequate return, scarcity of federal and philanthropic funding, racial and ethnic discrimination, and a pervasive spirit of hopelessness among the residents themselves.

So, why is persistent poverty higher in rural areas? There is no single answer. Among the factors are population loss/lack of density, lack of infrastructure such as transportation, absence of services, a history of natural-resource extraction without adequate return, scarcity of federal and philanthropic funding, racial and ethnic discrimination, and a pervasive spirit of hopelessness among the residents themselves.“But too many discussions start with the problems and stay there,” says David Dangler, director of NeighborWorks’ Rural Initiative. “Hope in the Delta, both the paper and the forum, take a look at examples of local and regional success stories and build from there. We want to have a powerful conversation about solutions.”

Indeed, in every challenge, there are insights and opportunities that can be exploited and in fact already have been in many cases at the local level. Here are the authors’ recommendations:

Change the conversation in persistent-poverty counties by achieving immediate, tangible results in “clusters.” Explains King: “It’s incomplete to talk about changing who we elect to office. Poverty is too deep for that. We must first create a ‘ripeness’ for demanding something different of ourselves and others. We have to take residents from ‘I don’t think anything will change’ to ‘I saw something change.’ Once we do that, residents will want to learn more, volunteer and become board members of local nonprofits.”

Research shows that when people can see a ladder for upward mobility, they do better. Role models who make this climb successfully, in their own communities, are particularly important for children.

Develop community leaders and link these authentic voices to complementary networks. Once residents believe that change is possible and they have a place in it, the next step is to identify those individuals who have the potential to be leaders and help them “blossom.” NeighborWorks has made this a focus, helping its network members develop residents as leaders through its Community Leadership Institute. The annual event brings together teams of residents selected by member organizations for leadership training and action planning. Following the meeting, NeighborWorks awards more than $200,000 to implement community-based projects developed by the participants.

“Giving people the information, skills and confidence they need to have a voice can change persistent poverty,” says Mitchell-Bennett. “It’s helping them come up with solutions, then using their personal power to force the company or public entity to do the right thing.”

Improve the efficiency and effectiveness of government programs so that state and national program designs are shaped by the communities intended to benefit. Funding should not be War on Poverty style, in which much of the plans and effort were generated “outside.” Nothing changes in communities without local leaders. Likewise, while matching grants can be useful, a more flexible, tailored approach is more valuable for benefitting the most economically challenged communities. One way to level the field is to ease the threshold requirements for applicants and set aside a portion of any allocation for exclusive use in persistent-poverty areas. For example, NeighborWorks’ grant funding, which is largely financed through a federal appropriation, is unrestricted with no matching requirement. Funding is distributed based on production and becomes of a catalyst for leveraging other funds.

Improve the efficiency and effectiveness of government programs so that state and national program designs are shaped by the communities intended to benefit. Funding should not be War on Poverty style, in which much of the plans and effort were generated “outside.” Nothing changes in communities without local leaders. Likewise, while matching grants can be useful, a more flexible, tailored approach is more valuable for benefitting the most economically challenged communities. One way to level the field is to ease the threshold requirements for applicants and set aside a portion of any allocation for exclusive use in persistent-poverty areas. For example, NeighborWorks’ grant funding, which is largely financed through a federal appropriation, is unrestricted with no matching requirement. Funding is distributed based on production and becomes of a catalyst for leveraging other funds. Promote investment using new models that leverage public resources with philanthropy and private equity. One place to start is by working with financial institutions to extend the benefit of the Community Reinvestment Act to more rural areas. The CRA was designed to encourage investment in the places where banks have branches, but there has been a lack of local offices in persistent-poverty rural areas such as the Mississippi Delta. HOPE has been assertive about turning that situation around by expanding into more remote areas. Further leveraging of the CRA also could help close the digital divide with more broadband access. Acknowledging that broadband internet connectivity is now considered a basic public utility such as electricity and water, federal agencies such as the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development have made access in the home a priority.

“We need to be more intentional about investing in communities to help them go from opportunity deserts to thriving places,” says Bynum.

Build and sustain consumer wealth, supported by educational initiatives, incentives, and social and community networks. Financial capability is a growing focus for all organizations looking to build wealth that can be transferred between generations. For example, a small-loan program provides an effective alternative to payday advances—a large and lucrative business in most persistent-poverty counties.

Create jobs by removing barriers, encouraging entrepreneurial business start-ups and anticipating emerging economic engines while reversing out-migration. Almost no other progress is possible without employment opportunities that can build wealth and thus intergenerational transfers. But they must be real jobs that fit the community. You can’t, for example, suddenly create a Silicon Valley clone in an area that traditionally was dependent on coal mining. Nonprofit community development organizations can help small businesses started by citizen entrepreneurs thrive.

Partner locally and regionally to achieve economies of scale sufficient to compete with more densely populated urban markets. All organizations and businesses in a community or region should look around and ask, what can we work on together? Do it intentionally, with an expectation of both shared risk and shared value. “Success breeds success. When people see their neighbor successfully running a business, they feel they can do it too,” says Cornelius.

Do all of these strategies, coordinated together, clustered in communities where they can have the most measurable impact. All of these tactics have been done before. And they are all needed. One alone won’t have the lasting impact required.