Earlier this year, a Baltimore-based nonprofit held a community forum on creating a black arts district. Reflecting on the discussion that ensued, the program coordinator for Maryland Citizens for the Arts described one of the prominent themes that emerged: “Longtime residents were seeing outsiders move into low-rent spaces to open new, arts-related businesses that didn’t involve or take into account the existing community...Existing culture and history risked being lost to the creation of these ‘new’ neighborhoods.”

Those concerns sum up why neighborhood revitalization projects, including those designed to attract artists, often are paired in the same breath with fears of gentrification—which can be loosely described as change that alters a community’s historic character and increases property taxes and rents, thus displacing longtime, lower-income residents. How to avoid that association was one of the most common questions/challenges posed by network members when NeighborWorks America leveraged funding from The Kresge Foundation to explore how local nonprofits are using/want to use creative community development—defined as “the use of art and culture to facilitate positive social, physical and economic changes in neighborhoods, towns, tribal lands or regions.” In this post, the initiatives of two nonprofits in the NeighborWorks network is shared to show how they are confronting the challenge of gentrification as they leverage the strengths of creative community development.

Those concerns sum up why neighborhood revitalization projects, including those designed to attract artists, often are paired in the same breath with fears of gentrification—which can be loosely described as change that alters a community’s historic character and increases property taxes and rents, thus displacing longtime, lower-income residents. How to avoid that association was one of the most common questions/challenges posed by network members when NeighborWorks America leveraged funding from The Kresge Foundation to explore how local nonprofits are using/want to use creative community development—defined as “the use of art and culture to facilitate positive social, physical and economic changes in neighborhoods, towns, tribal lands or regions.” In this post, the initiatives of two nonprofits in the NeighborWorks network is shared to show how they are confronting the challenge of gentrification as they leverage the strengths of creative community development.

Using art to foster dialogue: Durham Community Land Trustees

DCLT in North Carolina is one of four network organizations that participated in a gentrification roundtable project organized by NeighborWorks’ Community Initiatives division. The project was designed to facilitate convenings of local residents to share their housing experiences and how the cycles of gentrification in Durham had impacted their lives.

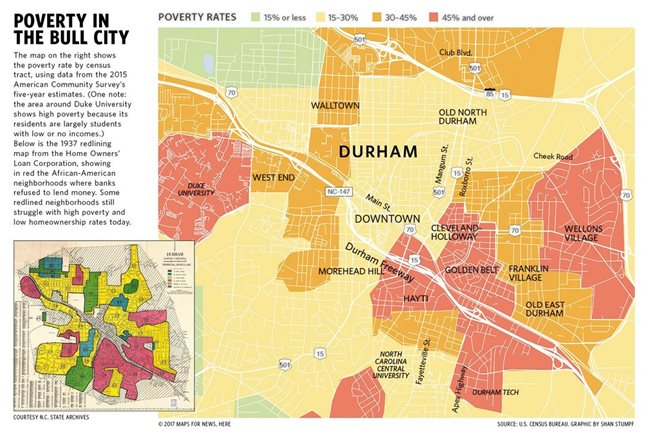

In Durham, where the housing market is undergoing a period of accelerated growth, some neighborhoods already have substantially gentrified. Thus, preventing that process elsewhere has become a priority for the mayor and city council. DCLT supported that effort by partnering with local nonprofit Bull City 150 (so named because the “Bull City” will celebrate its sesquicentennial next year) to use art, including an exhibit on housing inequality, to facilitate four roundtable discussions. DCLT focused on three neighborhoods adjacent to several others that already had experienced significant housing-cost escalation, hiring a local artist/facilitator and team of educators-researchers to develop a series of sessions titled “Tapestries of Home.”

The events incorporated elements of a newly developed Duke University exhibit on housing inequality called “Uneven Ground: The Foundations of Housing Inequality in Durham.” It weaves together text, interactive maps and photos to trace the area’s history of policies and other decisions that have exacerbated disparities between whites and people of color in the city.

Features included “rephotography,” which compares archival and modern-day photos; “Wanted in Our Neighborhood,” where participants created art illustrating the types of buildings they wanted to see in their neighborhood; “People's Story Station,” which encouraged attendees to record interviews with each other about their neighborhood; and “the People's Policy for Resilient Communities,” groups focused on drafting strategies to tackle Durham’s housing, displacement, eviction and deportation crisis.

Executive Director Selina Mack recounts hearing the story of one longtime resident, whose family had lived in the neighborhood for generations, who lost his home through eminent domain and demolition as part of a redevelopment project decades ago. He was promised his home would be rebuilt after the redevelopment was complete. So, he moved nearby and walked every day to the vacant lot where his home had been, never giving up on the hope he would be able to move back to the neighborhood. Eventually, however, he grew old and died.

These resident stories were recorded, like this one of Hazeline Umpstead, to document the deep, multigenerational ties. The process was cathartic for the residents and informative for DCLT staff, who now have a deeper understanding of the history—both good and bad—of the neighborhoods in which they work, as well as strengthened relationships.

Revitalizing—equitably—through art: Community Ventures

Community Ventures was founded 36 years ago in Lexington, Kentucky, to help state residents improve their financial health. The board and CEO Kevin Smith have chosen to particularly focus on helping individuals start and maintain their own businesses and purchase their own homes. Art and artists have become key to the former, and many coordinated activities are in place to assure existing residents can afford to do the latter.

Community Ventures was founded 36 years ago in Lexington, Kentucky, to help state residents improve their financial health. The board and CEO Kevin Smith have chosen to particularly focus on helping individuals start and maintain their own businesses and purchase their own homes. Art and artists have become key to the former, and many coordinated activities are in place to assure existing residents can afford to do the latter.As part of its microenterprise and entrepreneurship work, Community Ventures has established several incubators—with the newest one being Art Inc. It was the brainchild of Mark Johnson, now its president, who is himself an artist. Although Johnson has worked for many years in the field of lending and economic development—including a stint supporting the state cabinet—he shows and sells glass art and photography, even exhibiting his pieces in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

“It was when I was working with the state’s economic development cabinet that I first really saw how artists need some assistance with the business side of their affairs,” he recalls. After he joined Community Ventures, Johnson went to Smith and the board one day with a proposal: "We're doing great things for food-based entrepreneurs with our Chef Space incubator. We're doing great things for small businesses with our office-space incubators. Can we do something for artists and creative entrepreneurs?" They responded, "Go do some research, come back to us and we'll see what we can do."

Johnson talked with about 40 artists who participate in the Kentucky Arts Council, and what he heard was a need for three services: 1) help in becoming better entrepreneurs, 2) support in getting exposure for their businesses, and 3) more platforms to actually sell their work. Thus, Art Inc. was born. Today, it is working with 42 artists, offering services from website design, to social media promotion, to video production, to sales via an online gallery and in-person exhibits. The services are offered for a fee, and eventually, Johnson expects Art Inc. to be a sustainable business enterprise itself.

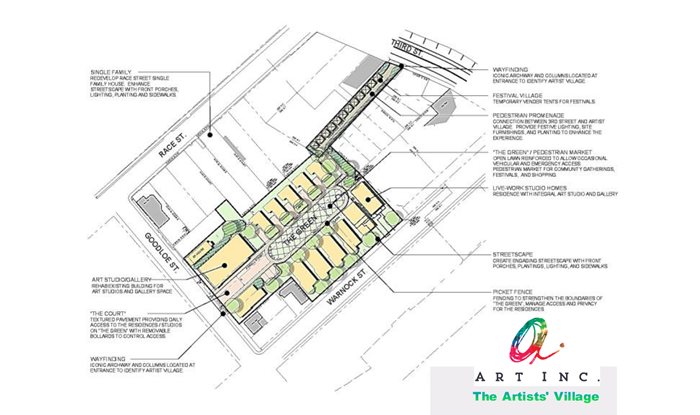

On the affordable housing front, Community Ventures is developing property on the historic, primarily African-American east end of Lexington, an area that needs “reinvigoration.” One of its projects there is an “artists’ village,” where 14 artists can purchase affordable homes with attached studios, using their own financing or loans from Community Ventures. The first buyer was Frank Walker, a local resident and the state’s first African-American poet laureate; he will move into the development in the summer. Johnson plans to move there himself as well. The resulting media attention has even attracted interest from an Ohio artist.

On the affordable housing front, Community Ventures is developing property on the historic, primarily African-American east end of Lexington, an area that needs “reinvigoration.” One of its projects there is an “artists’ village,” where 14 artists can purchase affordable homes with attached studios, using their own financing or loans from Community Ventures. The first buyer was Frank Walker, a local resident and the state’s first African-American poet laureate; he will move into the development in the summer. Johnson plans to move there himself as well. The resulting media attention has even attracted interest from an Ohio artist.The artists’ village is part of a larger Community Ventures project in the east end, which will bring much-needed new retail business and housing into the area. And the nonprofit is very aware of the gentrification-related concerns.

“We've had numerous conversations about how we can avoid and mitigate the negative aspects of gentrification,” says Johnson. “We held many meetings with community leaders, participated in homeowners’ association meetings and hosted a town-hall forum as well. We wanted to make sure neighborhood residents knew our plans and give them an opportunity to offer input and feedback, to say what they needed and wanted. And we incorporated what we heard, even regarding what the buildings will look like.”

The artists’ village, in particular, was well received, due to the nonprofit’s focus on reaching out to locals who had been creating in their living rooms, bedrooms and basements. In addition, as part of the overall development plans, Community Ventures is offering affordable mortgage financing, assistance with down payments and closing costs, and the education needed to be a long-term successful homeowner.

“We haven't seen any negative aspects of new people coming into the neighborhood,” reflects Johnson. “Open conversation is important to expose and plan for any possible negative outcomes, such as increasing property values, taxes and rents. But we all realize that our neighborhoods need to grow and change so we can offer more opportunities for everyone. The addition of the artist studios, and new retail, will bring individuals into this community who normally would not venture here. And when they come, they will spend money. That will help reinvigorate the neighborhood, build it back up.”