It's been 30 years since the Eastern Shoshone Housing Authority (ESHA) built brand new homes on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Fort Washakie, Wyoming, the seventh largest Indian reservation in the country.

But homeownership has long been considered a pathway toward wealth. So when, after years of funding barriers, ESHA applied for and received an Indian Housing Block Grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, they decided to use the $4.2 million grant to build new homes on the reservation.

The houses, the first major construction since revitalizing Tigee Village in 2014, will become home to families who will rent them, while preparing to build on their own home sites, says Gilbert Riche, ESHA's resident services director. The housing authority has identified families — current renters who make moderate to higher incomes — who would be likely to qualify for a mortgage.

“We'll help them improve credit capacity by reporting their rent to the credit bureaus," he says. "We'll help them build to mortgage readiness." When they move to the new homes, part of the tribe's Choice and Change program, their previous rentals will become available to families who are on a waiting list.

Riche estimates at least 80 families are on the list waiting for affordable homes. Hope White, ESHA's deputy executive director, says it can take two to three years to get off of that list, and that overcrowding is a big issue.

When the new homes are complete this spring, the tribe will begin construction on 15 new homes in a second subdivision — Black Horse subdivision. Those homes, which also received funding through a development block grant, will come with a five-year loan assumption. That will allow ESHA to recoup enough funds to initiate another project, Riche says.

To prepare families for homeownership, ESHA wanted partners. They met Melissa Noah, executive director of Wyoming Housing Network, a NeighborWorks network organization, at exactly the right time.

Forming a partnership

Melissa Noah got the call from ESHA over a year ago when the organization was preparing to apply for Homeowner Assistance Fund (HAF) money to help residents and saw the suggestion that they connect clients with a HUD-certified counseling agency. Wyoming Housing Network (WHN) was the only HUD-certified housing counseling agency in the state. While using the housing counselors was not a hard-and-fast requirement, once ESHA and WHN met, it became clear that WHN could be of service.

WHN started by working with tribal members on foreclosure prevention. Then, the conversation turned

Wyoming Housing Network provides a statewide first-time homebuyer program. They could provide culturally relevant education, credit counseling, information on how to go through the homeownership process, information on how to take care of a home and more. The partnership determined they could do so while families were already in ESHA's rental housing program. "Our counselor could work with families for one to five years, so that by the time they signed mortgage papers, the families would be equipped and informed," Noah says.

To prepare for working with Native families, ESHA asked Noah to attend a National American Indian Housing Council (NAHIC) conference to learn more about Native housing. Noah used the Native Partnership Grant from NeighborWorks America to send three staff members to the conference. She also connected with Mel Willie, NeighborWorks' director of Native Strategy & Partnerships, and the two met with ESHA together."It solidified that we have access to resources, that we have support and momentum behind the work we can do as a housing agency to support their goals for housing as a tribe," Noah says.

For Willie the partnerships, a key part of NeighborWorks' Native strategy, could not be more important. "For organizations that are either neighboring tribes or have significant tribal populations in their service area, it's their responsibility to provide programs and services to tribal communities," he says. "If you look at it through a racial equity lens, that should be a priority."

"It's been an exciting process," said White from ESHA.

Noah and several staff members earned NAIHC's Pathways certification, which instructs tribal housing and financial education professionals on how to teach homebuying to prospective native homebuyers. Members of Wind River Development Fund (WRDF), another partner, also took the course.

When it was time for WHN to hire a new housing counselor, the organization wanted to do so in a way that best served the tribal community. Through a collaborative effort with ESHA and WRDF, they hired Martin Armajo Sr., a Northern Arapahoe tribal member with a background in real estate.

"He's familiar with the challenges that we face out here," White says.

Finding the right counselor

After a 20-plus-year career in law enforcement, followed by a few years as an associate judge, Martin Armajo Sr. was looking for a new job. During his years patrolling the Wind River Indian Reservation, he saw the need for better housing. "I've always seen the need. But as I was patrolling the reservation, I went into many homes," he shares. He saw large, extended families in small spaces. He saw homes in need of repair.

His father had spent his life working for reservation housing authorities, first at Wind River Housing

Once Noah offered him the job, Armajo asked for one more day to think about it. "I said a little prayer. And I said, 'If I'm doing the right thing, Dad, give me a sign.'" That evening, when Armajo and his daughter were cleaning out a storage unit, they found an item covered in bubble wrap.

“I took it off," Armajo says. "And inside was a plaque presented to my dad from HUD, an award for an excellence for his work." On the plaque were the words: Remember a man does not leave this earth util the last person that remembers him is gone.

“I said, 'There's my sign. Thank you, Dad.'" He started the job in early August. Since then, he's been taking classes, preparing to counsel those interested in buying a home, to teach courses and more.

Because he owns a home on the reservation, Armajo knows a lot of the bureaucracy and barriers to homeownership. "There are challenges with bias," he explains. "A lot of banks won't deal with us because we're not on fee land, we're on trust land." There's a housing shortage on the reservation, and a shortage of contractors to do the work. But with the team of partners, he has a lot of hope, he says. Last month, he, too, went through Pathways training and received certification. He plans to begin teaching his first homeownership class in December.

His hope, he says,"is that once we get things going, things will change."

“A lot of families have already reached out to him," shares White.

Noah had expected that to happen."Based on community discussion, we are confident that once he's open for business, he will be very busy helping people reach their housing goals."

Building the program

The Choice and Change program is still, of course, brand new. But the partners see it as a sustainable program that will continue. And they're committed to the same vision.

“We want to be a part of and support the housing industry on the reservation," explains Erika Warren-Yarber of Wind River Development Fund. "It's so needed, especially when we talk about the

The organization offered office space to Armajo, so that he could have a central place to meet with people and be available to community members. (WHN's main offices are more than two hours from the reservation.)

WRDF's Paul Huberty says the primary goal and mission is to bring capital to the reservation,"to people who don't have access to money or loans or even banks."

When they discussed with WHN and ESHA the housing work that needed to be done, he says,"we realized we all want to do the same thing. My goal is that in the next five to seven years, we can drive across the reservation and feel a renewed sense of hope."

Warren-Yarber, who lives in Riverton, a town bordering the reservation, talks of some of the restrictions and bureaucratic hurdles her family and other tribal members have had to face when it comes to housing."There are so many things that were put in our way as Indigenous people in the homeownership realm. There are so many hoops to jump through and there's such a lack of understanding."

Her organization, she says, stands ready to help people understand through financial literacy and coaching and more — both Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapahoe. "We're here to support the whole reservation."

Noah says the same. Last month, WHN held a board retreat on the Wind River Reservation. They toured ESHA's new homes and cultural community centers. They hosted a dinner that turned into a community forum, where families came and talked about housing issues and barriers to housing on the reservation. They are excited to begin the first classes.

The tribe is excited, too."Together we're going to figure out how to alleviate some of those barriers and make it streamlined for homeowners," Riche says.

Hope for the future

White's own hope for the program is simple: "Families buying homes."

Riche wants to see the path to homeownership for tribal members become more accessible, streamlined" and culturally relevant, with us guiding them along the way."

And Noah's hopes align. "We want to help with the change," she says.

Education is key — not just for homeowners, but for lenders who may not understand how loans work on tribal lands. "We hope to be able to demonstrate that our homeowners should qualify for multiple lending products," Noah says."This is how we can collaborate and work together."

Currently there is little lending happening on the reservation, even with the section 184 loan program, a mortgage product designed to facilitate homeownership and increase access to capital in Native communities.

“We're going in to help people meet their housing goals," Noah says. "That matches ESHA's and WRDF's goals. We're looking at the whole spectrum on housing: How can we have an impact? How can we be a good partner and support the tribes' goals for change?"

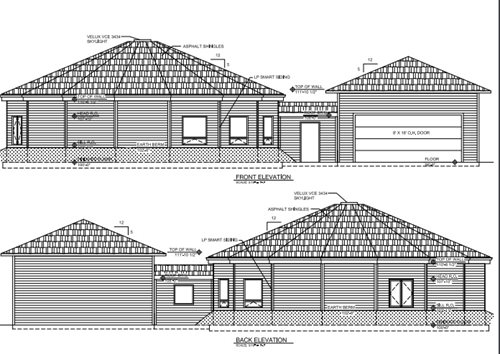

If you walked through the neighborhood right now, the change would be apparent, White says. Five factory-built homes have been purchased and are sitting on foundations near four site-built homes that are under construction.

“It's a beautiful sight to see," says White. "They're brand new and the Rocky Mountains sit right outside their front door."

Building these homes is adding jobs to the community, too, adds Riche. ESHA also reached out to the youth job corps with further training opportunities.

A housing conversation

Noah says the relationship has grown mostly because of ESHA's willingness to invite them into the conversation. They wrote some grants together, and while they did not all come to fruition, the process helped them realize how much their goals were aligned.

"There's so much pressure on housing right now," Noah says. "There's so much need. Everyone is looking at equity work which has everyone looking at housing on tribal land at a national level. There's more energy around it – a higher level of urgency. We hope this means more resources for change."

The timeline for creating change is long. But all partners involved say they're willing to work for a sustainable program that will continue to create homeownership opportunities.

As the only NeighborWorks network organization in the state, Willie says WHN "realized that the Native population was where they must extend programs and services – that the tribal community was the community that was the most underserved." (Updated statistics remain a problem, though Noah says she hopes to help collect data that will provide insights at the program continues.)

Partnering with tribal communities and seeing "where they can be of service" is part of NeighborWorks' Native Strategy. It led to providing 38 grants to organizations that have been making such partnerships happen over the past three years.

“The investment in tribal communities is not meeting the overwhelming need for housing and homeownership," Willie explains. "It's important that NeighborWorks looks at helping tribes leverage the federal dollars by providing programs and services through partnerships to meet those unmet needs. I think that's a key role of the NeighborWorks' Native Strategy."