The news is awash with the damage wrought by hurricanes Harvey and Irma. But these natural disasters should not have surprised anyone; they are only the latest in a string of worsening weather events that is expected to continue.

In one report, researchers predict that almost 670 coastal communities will endure chronic flooding by the end of the century. That would mean that by 2100, tidal flooding would hit more than 10 percent of useable land an average of twice a month, affecting 60 percent of communities on the East and Gulf coasts and a smaller number on the West Coast. By 2035, they predict, just a moderate sea-level rise will chronically inundate nearly 170 coastal communities.

The increase in severe weather-related events is not limited to storms and flooding. A 2016 Climate Central analysis found that the annual number of large wildfires exacerbated by drought has tripled since the 1970s and that the amount of land they burn is six times higher than it was four decades ago. According to the organization, more than 37,000 fires have burned more than 5.2 million acres across the country since the beginning of the year.

And then there are prolonged high-heat spells. Researchers reporting in the Scientific American found that the number of “extreme heat event” days (three or more successive days in which the 24-hour daily mean temperature rise above the historical average high) had risen threefold from about four in 1980 to nearly 12 in 2013. “That means it is staying hot all day and all night, with no relief for three or more days,” said one of the researchers. “What’s perhaps the most important for heat stress in these urban environments is what goes on at night. It’s the cooling at night that’s important for the elderly and others who are not living in air-conditioned circumstances.”

Clearly, what’s needed is a systematic approach to anticipate and manage through these inevitable crises—ideally not just “bouncing back” but “leaping forward.” However, the challenge is to define just what “forward” means. That was the focus of a research paper presented at the Philadelphia NeighborWorks Training Institute by Gramlich Fellow Caroline Lauer.

Quoting the book “The Politics of Resilient Cities: Whose Resilience and Whose City?,” by Lawrence Vale, she asked, “Who bears the brunt of the crisis and whose interests are best served by the proposed interventions? And, if resiliency is bouncing back, what are we bouncing back to? In too many of our communities, there already is entrenched inequality. Will we bounce back to more of the same? Shouldn’t we be asking more of resiliency than that?”

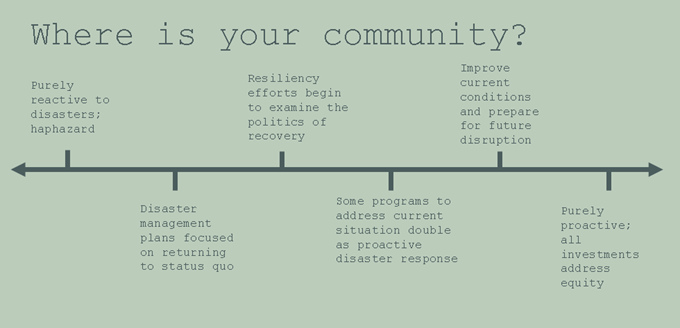

In the past, noted Lauer, there has been a driving belief in humans’ ability to control the effects of natural disasters; however, that has proven to be expensive and false. Today, there is a rapidly growing recognition that these “events” are inevitable and the focus must be on fostering resiliency to mitigate the damage. There also is a focus on the unequal sharing of disaster risk and the competing interests and stakeholders at play. There’s even been some conversation around creating a resiliency grading system, rather like LEED for energy efficiency.

“It’s more than a search and rescue mission. It’s the interrogation of the complex intertwinement of power, rights and justice with the objective of ensuring human security beyond mere survival,” write Nandini Gunewardena and Mark Schuler in “Capitalizing on Catastrophe: Neoliberal Strategies in Disaster Reconstruction.”

Case study: CDC of Brownsville

So, just how are NeighborWorks network organizations rising to this challenge? In “NeighborWorks Works: Practical Solutions from America’s Community Development Network,” the initiatives of the Community Development Corp of Brownsville (CDCB), Texas, is featured.The nonprofit serves one of the poorest regions in the country, the Lower Rio Grande Valley along the border with Mexico, where one in three people live below the poverty line. The landfalls of hurricanes Rita (2005), Ike (2008) and Dolly (2008), which wrought $2 billion in damage, exposed the need for programs to fill in the gaps left by federal, state and local governments. .

CDCB created the Rapid Disaster Recovery Housing Program (RAPIDO) with a network of five partners to address three of the biggest obstacles: slow transition from disaster response to housing recovery, the lack of a process for assuring that marginalized families connect with the appropriate resources and the lack of pre-disaster planning.

Transition: Eighty percent of Dolly-related FEMA claims were denied due to “deferred maintenance.” FEMA Spokesman Charles Powell claimed that, “A lot of the homes were built from second-hand materials, so the damage was, in most cases, caused from the faulty building of the house and not the storm.” However, in February of this year, a judge ruled that FEMA acted illegally. CDCB helped fill the gap left by FEMA.

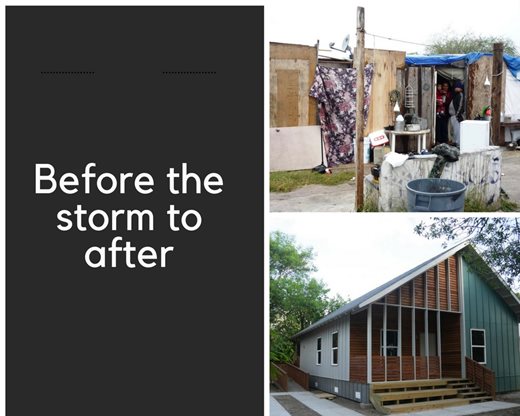

RAPIDO uses a temporary-to-permanent strategy, with a goal of providing immediate housing only as a first step to a permanent home. The coalition designed and built 21 prototype homes to test a scalable solution that allows families to move into a new home within four to six months (rather than the six years the previous local, state and federal response required). RAPIDO shrinks the timeframe by constructing a “core” building (about 480 square feet) on the resident’s lot, a basic structure that can easily be expanded once full recovery is underway. The pre-fab construction is assembled on site, by hand, in four days. Preliminary data show that structures that cost $70,000 to build are evaluated at $90,000 once complete—building wealth for each family. In addition, RAPIDO pre-procures all of the supplies and labor locally. This is a vital economic development driver.

Resource connection: Low-income families affected by a natural disaster find it difficult to navigate the process of applying for assistance. Through RAPIDO, each family is assigned a “navigator” who acts as their primary contact through the entire recovery process. A local eligibility-assessment team determines if a family qualifies for assistance and works closely with their navigator. These local leaders build the community’s social capital, continuing to advocate for residents once disaster recovery is over. For example, one of the local partners won a hard-fought effort to install street lighting throughout the colonias, and many of the individuals responsible were trained in the navigator program.

This emphasis on building social capital through engagement of resident leaders is shared by Neighborhood of Affordable Housing (NOAH). Its home is East Boston, a collection of five islands joined by a 19th century landfill project; the neighborhood is surrounded on three sides by water and has no land connection with the rest of the city. This makes it particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and coastal flooding, as well as almost-total isolation. Many of the residents are poor, non-native English speakers. NOAH recruited university climate experts to host technical briefings in the residents' native languages, offering education on issues such as climate change impact science and how to influence policymaking. Residents were invited to a series of community-planning workshops to collaborate with local agencies and departments on action plans for Boston's resiliency initiatives. To boost attendance, NOAH provided free food, childcare and translation for residents, many of whom work two or three jobs at or below minimum wage.

This emphasis on building social capital through engagement of resident leaders is shared by Neighborhood of Affordable Housing (NOAH). Its home is East Boston, a collection of five islands joined by a 19th century landfill project; the neighborhood is surrounded on three sides by water and has no land connection with the rest of the city. This makes it particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and coastal flooding, as well as almost-total isolation. Many of the residents are poor, non-native English speakers. NOAH recruited university climate experts to host technical briefings in the residents' native languages, offering education on issues such as climate change impact science and how to influence policymaking. Residents were invited to a series of community-planning workshops to collaborate with local agencies and departments on action plans for Boston's resiliency initiatives. To boost attendance, NOAH provided free food, childcare and translation for residents, many of whom work two or three jobs at or below minimum wage.Pre-disaster planning: The RAPIDO model starts recovery activities when no disaster is underway by creating a catalog of house designs that residents can choose when rebuilding begins. RAPIDO handles procurement of permits from city and county agencies and trains contractors to build, store and reconstruct core units. It also trains organizations and individuals as navigators.

---

Dictionaries define the “ratchet effect” as the “declining ability of human processes to be reversed once a specific event (disaster) has happened.” Lauer concluded her presentation by advocating for an effort to create a “fireweed effect” instead.

“Has anyone here visited the western region of the U.S. after a wildfire?” she asked. “I used to live in Montana, and wildfires are a way of life. After a wildfire burns through an ecosystem, there’s a small group of species that are the first to return. They’re called pioneer species, and perhaps the most famous (and certainly the most beautiful, in my opinion) of these is fireweed. Fireweed is the first step of an ecosystem’s regeneration. I like to think of progressive resilience as fireweed. When we use a systems-based approach to think holistically about resiliency-related investments, making sure they address untenable social dynamics that exist before a disaster and leverage them to be sure we leap forward instead of bounce back, we sow the seeds for a more just society that will blossom after disaster strikes.”

“Has anyone here visited the western region of the U.S. after a wildfire?” she asked. “I used to live in Montana, and wildfires are a way of life. After a wildfire burns through an ecosystem, there’s a small group of species that are the first to return. They’re called pioneer species, and perhaps the most famous (and certainly the most beautiful, in my opinion) of these is fireweed. Fireweed is the first step of an ecosystem’s regeneration. I like to think of progressive resilience as fireweed. When we use a systems-based approach to think holistically about resiliency-related investments, making sure they address untenable social dynamics that exist before a disaster and leverage them to be sure we leap forward instead of bounce back, we sow the seeds for a more just society that will blossom after disaster strikes.”