Rose Espinoza grew up in the Corona Camp neighborhood of La Habra in Orange County, California. When NeighborWorks Housing Services constructed new houses on her old street in the early 1990s, she bought one. Her purchase was built, in part, on the good memories of her childhood, like her mother sewing costumes for participants of the Our Lady of Guadalupe Parade. "I wanted my son to have those same memories," she says. "But when we purchased our home, things had changed."

Gang activity in the neighborhood heightened everyone's fears. But Espinoza wasn't going to move again. She knew she had to take action and urged neighborhood kids to get involved in activities like volleyball. "I thought: If they do something positive, they won't be bored or think about hanging out with gang members," she said. "It was trial and error."

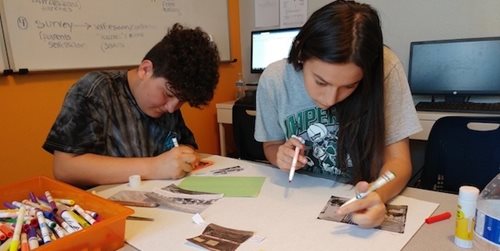

The activity that seemed to work best was the tutoring program she started in her garage. Other neighbors offered their garages, too, especially at homes where the parents didn't speak English and had a harder time assisting their children with homework.

Espinoza kept experimenting. A couple of days after she talked with the police about setting up a neighborhood watch program, she found her husband's truck was covered with graffiti.

"Don't finger us; keep your mouth shut," it said in Spanish. "He drove to work like that," Espinoza says of her husband. "When he came home, I met him with nail polish remover."

The gang members watched them clean. When they were done, Espinoza walked across the street. "Get used to my face," she told them. "I just bought this house. I can't sell it. I'm not going anywhere."

She also told them about the garage tutoring program, helping neighborhood kids. "I said, if you want to get your GED, I'll find a way of getting it done in the garage as well." And that's how she started making headway. If she heard someone was upset with her, she offered to talk with them. The gang members from the house across the street didn't come for GED training, but others from the home came in for tutoring.

She also told them about the garage tutoring program, helping neighborhood kids. "I said, if you want to get your GED, I'll find a way of getting it done in the garage as well." And that's how she started making headway. If she heard someone was upset with her, she offered to talk with them. The gang members from the house across the street didn't come for GED training, but others from the home came in for tutoring.

Eventually, she said, "they decided to leave us alone." Studying happened. Progress happened. Espinoza called the tutoring project "Rosie's Garage," and she was recognized for her efforts with a Dorothy Richardson Award for Residential Leadership in 1992, the first year NeighborWorks America presented the awards to leaders who used their energies and talents to bring about positive change in their communities.

Espinoza didn't know she was receiving it ahead of time. She had won a plane ticket and decided to go to Washington, D.C., with her family, she says. Neighborhood Housing Services of Orange County, the organization that built her home and supported her after-school tutoring program, suggested she drop by a NeighborWorks America dinner while she was in the nation's capital.

"I didn't know it was for me," she says. "It was all so surprising, how a little garage could be recognized all the way over there. It inspired us to be able to know we were on the right path and we were an example for everyone." It made her feel that she could conquer whatever came next.

Other awards came, too, and that is not so surprising. Rosie's Garage changed her community.

Espinoza received calls from TV stations, Reader's Digest and People Magazine. Today, the project she started is a certified nonprofit that has been featured in Women's World, O, The Oprah Magazine, and the New York Times. Espinoza won the Points of Light Presidential Service Award from President Clinton in 1994.

Espinoza had only intended to run Rosie's Garage for two years. But the kids would gather outsider her gate and ask when she was going to open "la escuelita." In 2005, when they'd been in her garage for 13 years, Espinoza left her job as principle designer of mechanical and electrical designing at Beckman Coulter to devote herself to Rosie's Garage full time. "Here we are, still offering tutoring to neighborhood kids," she says. "It's so simple, anyone could do it, really. You could gather and do homework in the park."

Espinoza had only intended to run Rosie's Garage for two years. But the kids would gather outsider her gate and ask when she was going to open "la escuelita." In 2005, when they'd been in her garage for 13 years, Espinoza left her job as principle designer of mechanical and electrical designing at Beckman Coulter to devote herself to Rosie's Garage full time. "Here we are, still offering tutoring to neighborhood kids," she says. "It's so simple, anyone could do it, really. You could gather and do homework in the park."

The changes in Espinoza's neighborhood were palpable. Kids finished school. Gang activity ceased. So Espinoza decided to experiment with the Grace/Pacific neighborhood, which had the highest rate of gang activity in La Habra. Neighborhood Housing Services had been creating homes there, too, she says, but they hadn't been selling as well. "Who wants to live in a neighborhood with gangs?"

So Espinoza expanded her program to the garage of a duplex. Again, she saw success. In 2018, there were only 25 police calls to that neighborhood; in previous years, there had been 1,000. "It's awesome to see that effect taking place in the neighborhood," she says. "It's been incredible to achieve all we've been able to achieve. It shows neighborhoods can change while addressing the needs of the residents as well."

In Orange County, people connected the dots and asked Espinoza to run for La Habra city council. "I said, 'I'm a resident leader, not a city leader.'" But she decided to run, part of a slate to make more changes for her community. The first few times she ran, she says, she lost. Then she hired a campaign consultant who told her to let people know who she was: the lady with the garage. In 2000, she won and she's been on the city council ever since. She currently serves as mayor of La Habra.

While she tells residents they don't need a college degree to become a leader, she always felt like she wanted to go back and finish working on her own. In 2020, she graduated from California State University, Fullerton with a degree in communications. In her neighborhood, she continues to talk to residents who want to become leaders, especially migrants. There's room for everybody, she says. "It's not one person."

While she tells residents they don't need a college degree to become a leader, she always felt like she wanted to go back and finish working on her own. In 2020, she graduated from California State University, Fullerton with a degree in communications. In her neighborhood, she continues to talk to residents who want to become leaders, especially migrants. There's room for everybody, she says. "It's not one person."

Her words of wisdom for other resident leaders? "We hold ourselves back," she says. "All of us hold ourselves back because we feel we don't have the proper education or the right monetary status. But I believe if we're willing to offer our time on any committee, in any neighborhood organization, we'll all learn so much."

If you do become involved, she says, "you'll have a stake in community. That's how neighborhoods change. It will require a little of your time. But the return you get is insurmountable."

Paul Singh, NeighborWorks' vice president for community initiatives, says the Dorothy Richardson Award for Resident Leadership recognizes outstanding leaders who have made a positive impact on their communities. The recognition highlights the critical role neighbors play in making their communities strong and connected.

While it recognizes past work, he says, NeighborWorks is aware that honorees like Espinoza continue to play leadership roles after they receive the award. "In fact," he says, "We've heard that the award has further motivated awardees to go back to their communities and redouble their efforts."

02/03/2021