In the media and at meeting tables, conversations about communities in need of attention typically center on distressed neighborhoods on the slide down or “hot” markets where gentrification is in danger of pushing out older, original residents. What’s missing from the strategy talks, says Paul Brophy, consultant and chair of the Legacy Cities Partnership, are “middle neighborhoods.”

“Even though these communities are not where the most vulnerable citizens live, nor where the evils of ‘filtering’ wreak the most havoc of blight and abandonment, they are the places where interventions may plausibly head off these worst-case situations in the future,” writes Brophy in the introduction to “On the Edge: America’s Middle Neighborhoods.”

Just what is filtering? What are middle neighborhoods? And why does Brophy think they deserve more of our time and investment, when there are so many of the most troubled communities clamoring for attention?

NeighborWorks America’s Community Initiatives’ team recently invited Brophy to answer those questions at a DC “brown-bag” event, and he will speak at a Tuesday afternoon workshop (4:30-6 p.m. Aug. 15, Washington A on the third floor of the Loews Philadelphia Hotel) at the upcoming National Training Institute.

Here are his answers and some food for thought:

Filtering

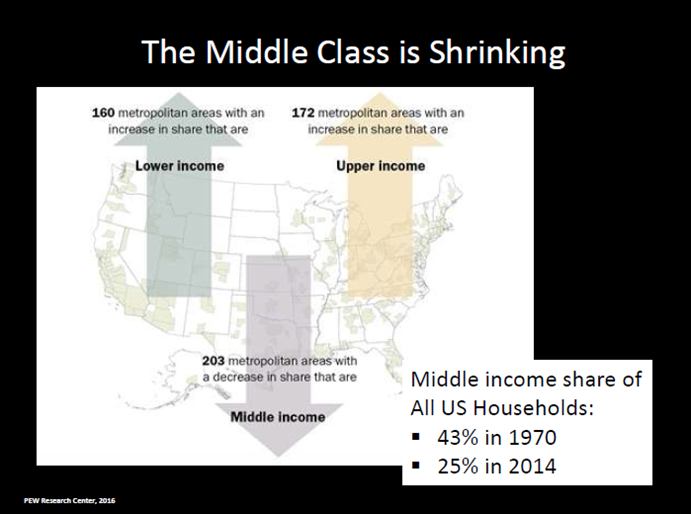

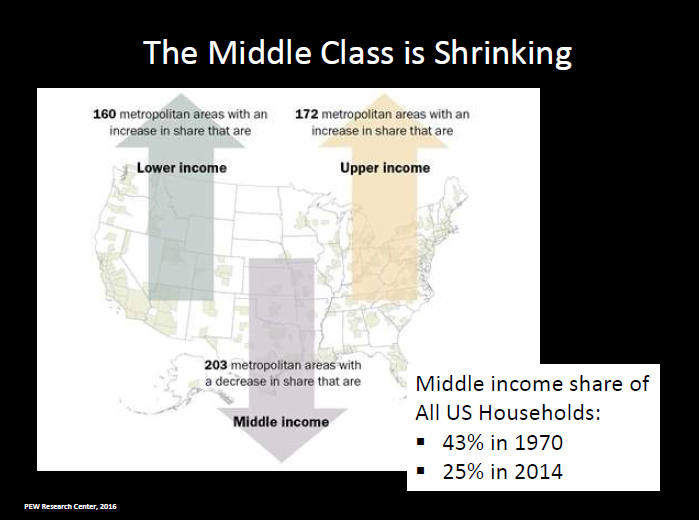

Filtering occurs when an oversupply of high-quality/high-cost homes on the fringe of a metropolitan area causes a decline in market value, allowing some families from the “rung below” to move in. That encourages other owners in the area to allow the quality of their properties to decline, in order to take advantage of the new market dynamics—often through insufficient upkeep. The result is a ripple effect across adjacent, less-expensive neighborhoods: an influx of households of somewhat lower financial means, along with a decline in the physical quality of the homes.“Once begun in a neighborhood, the filtering process at some point is likely to cross a threshold: a critical point past which change accelerates—causing a downward spiral,” Brophy explains.

The focus of his book, in fact, is how to best stop this process. He believes the best point of intervention is the “middle neighborhoods.”

Middle neighborhoods

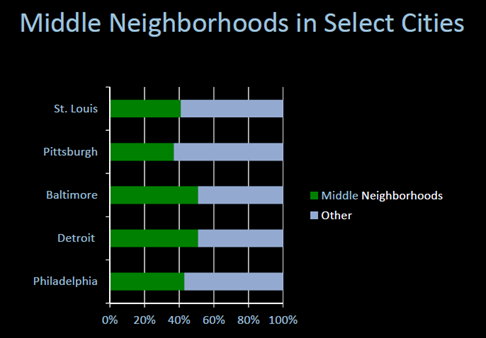

There are two broad types of cities: One is growing in population, employment and income per capita; the other is struggling. The latter type is made up of “legacy cities,” writes George Galster, a professor of urban affairs from Wayne State University and a contributor to Brophy’s book. Within legacy cities, there are three types of neighborhoods. At one extreme are those that offer a high quality of residential living. At the other end of the continuum are communities marked by decay and impoverishment. And in between…there are the middle neighborhoods. “Middle neighborhoods are on the edge between growth and decline,” Brophy explained at his DC roundtable. “These are neighborhoods where housing is typically affordable and in acceptable condition, and where quality of life—measured by employment, crime and school performance—is sufficiently good that new homebuyers are willing to play the odds and choose these neighborhoods over others in hopes they will improve rather than decline.”

“Middle neighborhoods are on the edge between growth and decline,” Brophy explained at his DC roundtable. “These are neighborhoods where housing is typically affordable and in acceptable condition, and where quality of life—measured by employment, crime and school performance—is sufficiently good that new homebuyers are willing to play the odds and choose these neighborhoods over others in hopes they will improve rather than decline.”However, at the same time there is a vulnerability: Property values often are flat and their value trajectory is not clear. While these communities are more racially diverse than both strong and distressed neighborhoods, the potential for decline is ever-present—unless effective intervention provides vital support.

Why focus on middle neighborhoods?

“Middle neighborhoods are in many ways in the most precarious position,” another chapter explains. “They are the areas that have the most to lose and the farthest to fall when confronted with continued strain on residential markets. One or two boarded-up houses on a bock can be the difference between a neighborhood on the rise or one falling into distress. This means that for cities with limited resources, investing in the middle neighborhoods can often produce the biggest returns.”It’s hard to argue with that rationale. But as one participant in the discussion asked, “Given NeighborWorks’ strategic ‘North Star’—our vision that every community is a community of opportunity—do we leave behind distressed neighborhoods? Our resources are not unlimited after all.”

It’s a question worth pondering, since “every community” means leaving no one behind. Each of our network organizations will need to strike the balance that best fits their geographic context, their expertise and resident feedback.

What kind of investments have the most impact?

The answer is straightforward, say the authors. All strategies must be designed to build residents’ confidence in the future of their neighborhood—when they feel pride in their homes, the real estate sells and rents successfully, and investment makes economic sense. Here, they say, are some of the tactics critical to achieving that goal:- Collect and use real-time data. Don’t rely on old census data or out-of-date ownership records. Invest the resources required to gather current market intelligence. NeighborWorks America can help, through its Success Measures tools, including its Community Impact Measurement survey.

- Respond to market realities. “Many middle neighborhoods were originally built to serve modest-income households. The offer traditional working-class housing that no longer young families who often desire more than one bath and two bedrooms. Other middle neighborhoods were built with big houses for large families and today are seen as too expensive to own and maintain,” the authors point out. Building a variety of housing types can make a neighborhood more accessible. For instance, Chattanooga Neighborhood Enterprise, Tennessee, has a history of introducing new housing types as part of neighborhood revitalization—typically to add density to offset increasingly expensive land costs. Currently, it is incorporating nine 800-square-foot homes (two bedrooms, one bath, selling for $115,000-$140,000) into its “missing-middle housing”—along with quads and duplexes.

- Identify and promote a neighborhood’s strength. Find out what makes the place special and what can be promoted and to whom—that is, what market segment might be attracted to the neighborhood. “People do not choose a neighborhood or choose to reinvest in their homes because the community no longer has certain problems; they choose a place because it offers something they want,” the authors stress.

NeighborWorksAmerica’s neighborhood marketing program is cited as successfully helping to promote community strengths through rebranding initiatives, infill projects, curb-appeal programs, etc.

- Forge relationships among neighbors. Too many middle neighborhoods seem to have lost the ties that once helped residents feel “connected.” That’s exactly what NeighborWorks America’s Community Building and Engagement team helps members focus on, through everything from resident leadership development to youth and senior programming.