When my oldest daughter was in first grade, she seemed to be in trouble virtually every day. Her teacher sent notes home complaining of her "fidgety, inconsiderate conduct," and when we had our first parent-teacher conference, she was chastised for an "oppositional attitude." Even more alarming, the teacher assessed our daughter's emotional and mental development as deficient. Meanwhile, my daughter had begun complaining of stomach pains every morning and the teacher was sure this was just her way of trying to get a ticket out of class. As a new parent who had been taught to respect teachers and that their word was, in essence, "gospel," I assumed my daughter, indeed, needed to be disciplined and brought into line.

However, my daughter was fortunate. Her physician, consulted about her stomach pains, advised that they were likely stress-induced. And as a parent, I didn't suffer from the poverty-induced shortage of "mental bandwidth" described by Eldar Shafir, PhD, co-author of "Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much" and a speaker at the December NeighborWorks Training Institute (NTI) in Washington, DC. Thus, I was able to take time off of work to figure out who else to consult and then spend time in meetings—becoming the "squeaky wheel that gets the grease." Her school district also was well-funded, which meant there was a qualified social worker who could conduct an independent assessment—and advised me (confidentially) that she believed the problem was not with my daughter, but with the teacher. My daughter had options; we switched her into a different type of class with a different type of teacher. What had started off as negative association with school and could have tainted her performance for life faded away, and today she is a college graduate with a successful career. Subtract those advantages, as is true for thousands of young people today, and the result is much different.

Education and income inequality

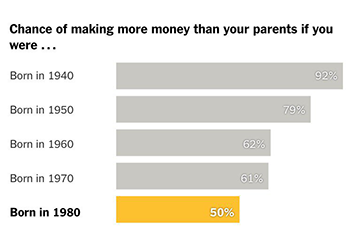

Education—or rather, lack of it—is one of the key drivers of the growing gap between this country's haves and the have-nots, says David Grusky, professor of sociology at Stanford University and director of the Center on Poverty and Inequality. Grusky, one of the featured speakers at the Seattle NTI this week, has led seminal research comparing economic health (you could call it the index of the "American Dream") between generations. The conclusion: Only half of individuals born in 1980—today's 36-year-olds—make as much money as their parents did. "We are at a crossroads in this country," Grusky says bluntly. "We've ever seen a gap in resources this large or as sustained. It's truly uncharted territory, and the stakes are very high. I'd say this trend is much more threatening than climate change, but it's not being treated that way."

"We are at a crossroads in this country," Grusky says bluntly. "We've ever seen a gap in resources this large or as sustained. It's truly uncharted territory, and the stakes are very high. I'd say this trend is much more threatening than climate change, but it's not being treated that way."In fact, in Jared Diamond's book, "Collapse," which studies societies that have imploded, one of the predictive factors is a growing "gated community" aspect to society, in which the affluent are insulated from the conditions and needs of everyone else.

In the United States today, that shouldn't be the case; the American economy is far larger and more productive than in 1980, for instance. Per-capita gross domestic product is almost twice as high. That increase should have allowed most children to be better-off than their parents. But they aren't, and the trend is getting worse. Why?

"There are two key forces at work," says Grusky. "One is that the rate of economic growth is slowing, so the total ‘pie' available to everyone isn't growing fast enough. And the second factor is the way in which we divide that pie up. A lot more is going to the relatively small percentage of affluent individuals—and that is simply inefficient—a total waste of productivity."

Research suggests that "division of the pie" has a much greater impact than lifting overall growth, and that's good news, since it is much more controllable. And one of the most significant ways to improve the lot of more people further down the income ladder is education.

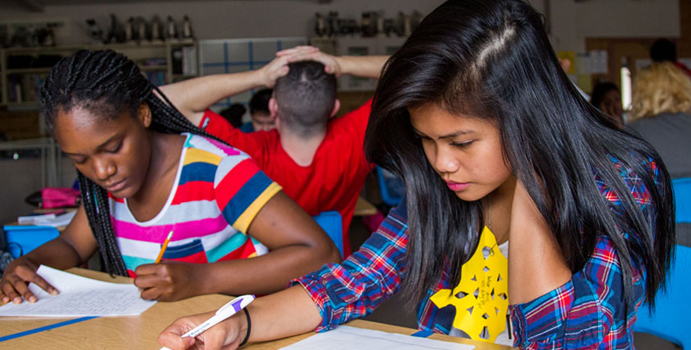

"The returns from a college education have increased," Grusky says simply. And there are a lot of factors that prevent university graduation for too many people, including many that start early in a person's life—like functionally segregated neighborhoods, parents mired in poverty, and poorly funded and staffed schools.

Support for parents and schools

Enter the Gates Foundation. David Bley, another NTI speaker in Seattle and director of Pacific Northwest initiatives for the foundation, explains two of its strategies: charter schools where they make sense and wrap-around support for traditional public schools where they don't."We see charter schools, which have gotten a lot of media attention, as just a tool used for a bigger goal," explains Bley. "The bigger context is that all children deserve the opportunity to be successful. The odds are simply not as great if kids are not successful as students. And getting there requires a lot of things."

Sometimes, he says, traditional public schools work and work well, primarily due to an affluent family base and a committed community. Other times, mostly in marginalized neighborhoods that have been "left behind," they don't. In Washington state, says Bley, the foundation has opened eight nonprofit charter schools in predominantly low-income communities, where residents are mostly of color and almost a quarter don't speak English at home. Although enrollment is open to all students in the district, with acceptances decided by lottery, "it's clear who we cater to," says Bley, by where we are located and to whom we market. We make a very intense effort to reach parents who need this option."

Opening and operating charter schools, however, are not most of the foundation's work in education. It also works to support the struggling public school system by bringing in a focus on the "whole child" through pre-school and afterschool programming, as well as parent-engagement and –support outreach.

"Low-income parents and parents of color have big dreams for their kids, but often have the least resources to make them real," he says. "They are too often working multiple jobs, struggling to make ends meet."

This is where housing and community-development organizations can make a real difference, by tying parent- and education-support activities directly into resident services and other types of programming and community planning.

Putting it all to work on the ground

One example is a project now in the works by NeighborWorks member Homesight in Seattle. "With the help of a Gates Foundation grant, we've been working since 2009 to analyze policies for social equity," says Executive Director Tony To. "But now we want to translate that work into actual programs and projects. And we knew we had to look beyond ‘bricks and mortar,' like education. Rents are high in this area and it's hard to assure sufficient affordable housing. But if we can equip children in historically marginalized communities with a quality education early on, then they will be able to compete better through high school, get better jobs and afford the rents."

One example is a project now in the works by NeighborWorks member Homesight in Seattle. "With the help of a Gates Foundation grant, we've been working since 2009 to analyze policies for social equity," says Executive Director Tony To. "But now we want to translate that work into actual programs and projects. And we knew we had to look beyond ‘bricks and mortar,' like education. Rents are high in this area and it's hard to assure sufficient affordable housing. But if we can equip children in historically marginalized communities with a quality education early on, then they will be able to compete better through high school, get better jobs and afford the rents."So, when Homesight was given an option on three and a half acres of land in southeast Seattle, right next to a light-rail station, it was seemed a perfect opportunity to take the next step. The result: the plan for the Southeast Economic Opportunity Center. The SEOC campus will have five main components, all in synch with the community plan that's been in the works for the past 12 years:

- Multicultural community center, where nonprofits pushed out by high rents can collaborate.

- Charter high school (operated by the nonprofit Green Dot Public Schools).

- Wellness center (in partnership with the local children's hospital).

- Early-learning (pre-school) program, which not only will provide multi-lingual support for immigrant children in the community, but also certify and employ many of the mothers providing local child care.

- Housing, comprised of both 80-120 percent area-median-income rentals and

- 60 percent AMI rent-to-own homes.

- Small-business retail, to encourage entrepreneurship.