Numerous studies have documented that early childhood education and other forms of support are critical to social development, resilience, self-esteem and ability to learn throughout the lifecycle. However, experience in the field also is increasingly demonstrating that positive results are maximized when at least one parent is nurtured right along with their children. The solution: two-generation (“two-gen”) programs.

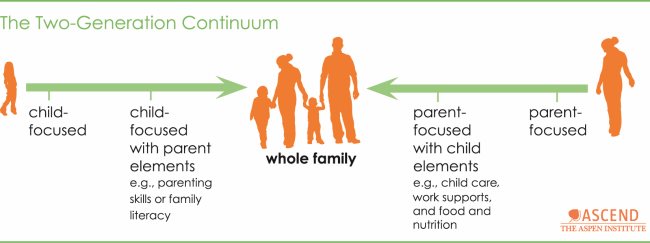

As these two-gen approaches evolve, they fall along a continuum from child-focused with some parental-involvement elements to parent-centered with child-oriented components. Although the lines can be blurred, some have a mostly economic security lens, others concentrate on mental health and still others focus on housing or the adults’ relationship with their children. No matter what, however, the operative words are “integrated” and “intentional.”

Here are two examples of how NeighborWorks network members are incorporating two-gen strategies to offer community children a “healthy start” in life.

Economic security: CAP Tulsa

As a community action agency, CAP Tulsa long has provided a range of services, including Head Start and early childhood education for children and a number of financial services for adults. “Then, in 2005, we began thinking about how we could make a greater difference in the lives of the children we were serving in early childhood,” notes Monica Barczak, Director of Strategic Partnerships for CAP Tulsa. “We decided to focus our resources on kids and their families, and we ended up shedding a number of lines of business and transitioning others to community partners—not an easy process.”

“Then, in 2005, we began thinking about how we could make a greater difference in the lives of the children we were serving in early childhood,” notes Monica Barczak, Director of Strategic Partnerships for CAP Tulsa. “We decided to focus our resources on kids and their families, and we ended up shedding a number of lines of business and transitioning others to community partners—not an easy process.”The central philosophy that shaped CAP Tulsa’s strategy going forward was this, Barczak explains: “Children can’t be the sole change agents. Early education and support is necessary, but not sufficient. And while parental involvement already is a central tenet of Head Start, we became influenced by research showing the positive effects for children of an increase in family income. So we began working on helping our parents attain a secure, predictable, sufficient source of income”—ideally, a job that can grow into a satisfying career. Since CAP Tulsa is anti-poverty agency, this focus aligns with its core mission.

CAP Tulsa currently serves 2,300 children from about 1,900 families. In any given year, says Barczak, about half of these are families are led by single parents— about 40 percent of whom are working full-time and 20 percent part-time. Among the households with two parents in the home, about three-quarters have at least one parent working full-time. Despite this, the majority of families fall below the federal poverty level and nearly all families served by CAP are considered low-income.

Thus, CAP Tulsa initiated CareerAdvance. Because local market data show strong demand for health care professionals, the nonprofit partners with the Tulsa Technology Center, which offers programs to train certified nursing assistants and other allied professionals. CAP Tulsa “buys” entire classes for its participants so the parents (mostly mothers, Barczak says, although they want to attract more men) can form social and support bonds. These bonds are strengthened through additional cohort meetings facilitated by coaches. Parents and children thus pursue their education together.

Thus, CAP Tulsa initiated CareerAdvance. Because local market data show strong demand for health care professionals, the nonprofit partners with the Tulsa Technology Center, which offers programs to train certified nursing assistants and other allied professionals. CAP Tulsa “buys” entire classes for its participants so the parents (mostly mothers, Barczak says, although they want to attract more men) can form social and support bonds. These bonds are strengthened through additional cohort meetings facilitated by coaches. Parents and children thus pursue their education together.“We try to remove as many barriers as possible,” Barczak says. CAP Tulsa pays all expenses related to the certificate program, and offers other supportive programming at the same time that their children are in Head Start classes. This includes financial coaching and ESL classes focused on the language skills needed to communicate with children’s teachers, doctors, the school district, etc. However, since most parents can’t commit to training for extended periods without earning income of some sort, CAP Tulsa has evolved to focus on relatively short-track programs. For example, the CNA classes are four to six weeks. Nine months is the longest.

To date, CAP Tulsa has funded CareerAdvance through grants, first from the George Kaiser Family Foundation (for the pilot) and now from the federal Administration for Children and Families (health profession opportunity grants). The latter requires structuring the program as a randomized, controlled study—meaning half of the parents who want to participate must be placed in a control group that do not receive services. Instead, they are offered referrals to other support services.

An analysis of results for the first year of the CareerAdvance model conducted by a group of university researchers is suggestive, with the caveat that at the time, participants were engaged in longer-duration training programs—thus delaying the return on investment:

- 61 percent of participants earned a career certificate, compared to 3 percent of parents in a matched comparison group.

- At year end, 49 participants were employed in the health care sector, compared to 31 percent of the comparison group.

- Children’s Head Start attendance over the year, a significant factor in their learning, was higher on average in families with participating parents than in the comparison group. The average rate of chronic absence (more than 10 percent of school days) was higher among children of comparison parents (65 percent) than among participants (48 percent).

Better parenting and involvement: Urban Edge

In Boston, 27 percent of young children live below the federal poverty level. So it’s no surprise that NeighborWorks member Urban Edge consistently heard from the families it serves that they needed access to programs that better prepare their children for pre-k/kindergarten. However, the nonprofit also heard concerns about the health of everyone in the family. According to the Centers of Disease Control, obesity in Massachusetts is significantly greater for blacks (34 percent) and Hispanics (31 percent) than it is for whites (22 percent). The disparities are similar with asthma: 17 percent of black and 13 percent of Hispanic children have asthma, compared to only 8 percent of whites. So, Urban Edge adopted a holistic program that aligned support for young children through pre-k readiness with programs for parents. Jumpstart provides the pre-k readiness and Families First provides parents with tools they need to become effective advocates for their children’s education. Local health facilities offer exercise classes, education about healthy eating, nutritional instruction and grocery shopping tips. In addition, every time parents attend a pre-K readiness class, they can check in via a Union Capital Boston smartphone app. They accumulate points for each check-in, which can be redeemed for gift cards and other prizes. Currently, participating children and parents meet separately two evenings a week.

So, Urban Edge adopted a holistic program that aligned support for young children through pre-k readiness with programs for parents. Jumpstart provides the pre-k readiness and Families First provides parents with tools they need to become effective advocates for their children’s education. Local health facilities offer exercise classes, education about healthy eating, nutritional instruction and grocery shopping tips. In addition, every time parents attend a pre-K readiness class, they can check in via a Union Capital Boston smartphone app. They accumulate points for each check-in, which can be redeemed for gift cards and other prizes. Currently, participating children and parents meet separately two evenings a week.“The most powerful outcome among the parents has been their social-support connections,” says Robert Torres, Director of Community Engagement. “They help each other now with babysitting and other needs.”

What’s interesting, says Torres, is that when surveyed, participating parents often rate themselves as less confident than they were before starting. Why? They now know they need to learn more!

“The key is to engage the families, to truly learn from what is happening in their lives,” says Torres. “And because partners are essential, you all need to be on the same page instead of overlapping services.”