Look at the classic stories we retell over and over again, at bedtime, around the campfire, on the stage and even on the news, and the common theme is conflict and contrast, good vs evil, perdition vs. redemption. (Think about some of the greatest stories of all time – The Wizard of Oz, Hamlet and even the way we spin our election coverage.)

“Businesses and organizations say they want true stories, to illustrate why a program is needed or the benefits of what they do,” he says. “But the thing is, you can’t control how true stories ‘land.’ The urge to make it ‘clean’—a perfect example of the point they want to make—is too strong. As a result, they scrub out the ambiguity. And the danger with creating such ‘shiny’ stories is that you do it so much you start believing it yourself.”

I can relate. Even as a journalist, I had an editor who asked, “where’s the villain?” and got impatient if I talked of nuances and shades of gray. When I transitioned into public relations and marketing, and was—at first rather shockingly—encouraged to “clean up” quotes, the search for the perfect poster person or case study became commonplace. Our jobs, after all, are to showcase particular arguments and favored solutions. But, as Simon points out, people are not always likable and their lives are messy and full of stops and starts. But if we only highlight individuals and situations that fit the ideal mold, does that really advance the common good?

Simon worked for the Baltimore Sun for 12 years (1982–95), covering crime and law enforcement. He saw people and their institutions at both their best and worst. Drawing on the insights he gained, Simon wrote “Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets” and co-wrote “The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood.” The first book was the basis for the NBC’s “Homicide: Life on the Street,” for which Simon served as writer and producer. He adapted the second book into an HBO mini-series called “The Corner.”

A common theme running throughout his work is the gritty realities at the heart of distressed communities—both the heroics we all love to share and the nuances and complexities that get in the way.

In a 2015 piece in The Washington Post, journalist Carlo Rotella wrote, “For two decades, Simon has been writing stories for TV about people who don’t transcend the economic, social and political systems and institutions that shape their lives. That makes him a rarity in Hollywood. What you typically see on the screen are heroes rising above circumstances through force of will, moral virtue, superpowers or some other kind of idealized potency. But Simon’s characters live within the structural limits of their world, so that their stories become an examination, often a critique, of that world. Thus, when they test the limits, they often find themselves outmatched.”

Community nonprofits can play an important role by sharing a fuller range of these stories, warts and all. It is only by doing so, along with the appropriate context—the structural and social dynamics that contribute to individual reality—that a deeper understanding and tolerance can be nurtured and lasting solutions found.

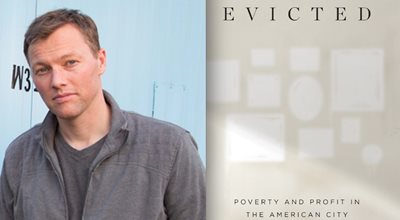

Matthew Desmond, another keynote speaker at the NTI and author of “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City,” does an excellent job of this in his book. When readers are first introduced to the tenants whose stories he shares, they seem irresponsible, ignorant and even downright unlikable. But as we delve deeper into their personalities and backgrounds, along with the often invisible complexities of structural power, who is “good” and “bad,” what is “right” and “wrong,” and the solutions to the problems posed no longer seem black and white. We grow to like some of the previously distasteful characters, and those we don’t we at least somewhat understand.

Matthew Desmond, another keynote speaker at the NTI and author of “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City,” does an excellent job of this in his book. When readers are first introduced to the tenants whose stories he shares, they seem irresponsible, ignorant and even downright unlikable. But as we delve deeper into their personalities and backgrounds, along with the often invisible complexities of structural power, who is “good” and “bad,” what is “right” and “wrong,” and the solutions to the problems posed no longer seem black and white. We grow to like some of the previously distasteful characters, and those we don’t we at least somewhat understand.Of course, Desmond told his stories and laid out his case over more than 400 pages. Nonprofits and their partners, as well as the media, don’t have that luxury. However, simply telling a variety of stories, and examining why some people stumble or fail despite our best intentions to help, is a community service and will contribute to the success of our mission in the long run.

Simon emphasizes that although it doesn’t make for an ideal story, failure and re-starts should be accepted and explained. For example, supportive housing and treatment programs for drug abusers should include beds for individuals who cycle in, out and back again. People and programs make mistakes. Likewise, support must be comprehensive. What’s the point of getting individuals out of prison sooner if they come back to “no job market other than the corner?” Simon asks. “They encounter the same problems they faced before, and very little else. There is nothing for them to do, no way to earn a paycheck. There is no meaning. Society has so little use for these types of people and it’s heartbreaking.”

That is exactly why in NeighborWorks America’s new, five-year strategic plan, the importance of surrounding affordable housing with cross-sector collaborations in the fields of employment, health, education, etc. is a central theme.

“The war against drugs didn’t work, and as a result, it had a profound effect on inner-city communities,” Simon says bluntly, adding that we have to be willing to admit our mistakes.

Too often, however, there is money to be made or won from the status quo. Simon also makes the point that it’s easy to avoid “inconvenient truths” when making arguments for change or support. For example, to win over conservative funders or policy makers, the argument is often made that drug treatment is less expensive than incarceration.

“The reality, though, is that there are costs associated with ratcheting down the drug war. And the same goes for many other issues related to urban policy, like desegregation. The more honest argument is to just say that what is being done is morally wrong. Economics isn’t all that matters,” says Simon.