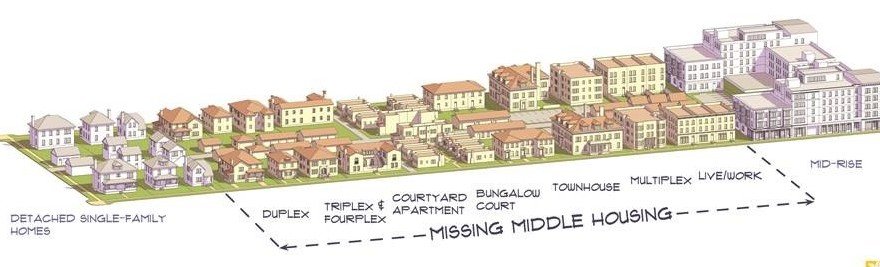

If you have ever visited some of the world’s greatest cities, you’ve probably felt a sense of vibrancy and excitement. There are many people on the street and businesses are thriving. These great cities all offer a variety of housing types, including single-family and small multifamily properties—such as duplexes, triplexes and quadraplexes. Owners often live in one unit with renters in the others. The density of the neighborhoods creates a solid customer base to support local businesses such as restaurants, coffee shops and stores. Sadly, the ability to recreate this type of neighborhood has declined with the growth of suburbs and a preference for single-family zoning. However, there is a movement afoot to bring back small-scale multifamily housing called “missing middle housing.”

Missing-middle housing is a mixture of multifamily homes with the look and feel of a single- family home. This housing type includes duplexes, cottages, bungalows and mansion apartments (four-, six- or eight-unit buildings).

Dan Parolek, a founding principal of Opticos Design and the person who coined the term “missing middle housing,” says there are a number of reasons people across the country are interested in the concept. He attributes the new desire for “missing middle housing” to a mismatch between the types of places people want and can afford to live in and what is actually being built and available.

“Nearly 60 percent of millennials and almost 30 percent of baby boomers are looking for ‘missing- middle’ choices. These are the two biggest market segments out there, and there is also a growing demand for walkable urban living, and missing-middle housing is a core piece of that,” says Parolek.

middle’ choices. These are the two biggest market segments out there, and there is also a growing demand for walkable urban living, and missing-middle housing is a core piece of that,” says Parolek.

In addition to an increased demand for walkable areas, a shift in household demographics is driving the desire for more missing-middle homes. Parolek says more than a quarter of all U.S. households are led by single persons and by 2025, the majority will not include children. Baby boomers who are empty-nesters and are downsizing, as well as millennials leaving their parents’ basements, will need affordable places to live.

“Our primary market no longer is that 1950s nuclear family with a mom and a dad and four kids. We’re needing to also think about the 30 percent of households that have just a single person,” adds Parolek.

NeighborWorks network member Chattanooga Neighborhood Enterprise (CNE) is getting ahead of the curve by laying the foundation to respond to demand for this type of housing. The organization recently invited Parolek and his team to Tennessee to help it get started.

“We believe the proliferation of these building types are an affordable strategy to increase neighborhood walkability, diversify building types and provide more naturally occurring affordable and mixed-income housing,” says Martina Guilfoil, president and CEO of CNE.

Don't confuse missing-middle housing with the tiny house craze. Tiny houses generally are no larger than 400-500 square feet, whereas missing-middle units start at about 650-750. Parolek says this type of housing should be viewed as “affordability by design.”

“Chattanooga is primed for the evolution of its neighborhood fabric through smaller residential housing,” says Bob McNutt, CNE real estate development manager. “However, many regulatory, financial and procedural barriers are restraining the marketplace from seeing a clear path forward into designing, constructing and managing these building types.”

Parolek adds that, “The sad reality is that there are a lot of obstacles, such as zoning, to building missing-middle housing and that’s part of the reason that they’re missing. We haven’t really built very many of them over the last 40 or 50 years.”

Chattanooga’s missing-middle housing will mirror the architectural character of the surrounding neighborhoods. The buildings also will be designed to be suitable for urban areas at a cost equal to or less than conventional housing types and be adaptable to changing conditions over time.

“The project will draw from the vast experience and design archive of the team members to pair historic precedent with floor plans that meet modern building code requirements,” explains Guilfoil.

Parolek adds that affordability by design is about scaling down and allowing a builder to construct three or four units on a site even when current regulations may only allow one or two. He says an example of this concept is a project planned for Richmond, California.

“We took a 100-by-100-foot lot and created a five-unit cottage-style design. Our economist tested the affordability and was able to show that a household with a median income of $45,000 could afford to either rent or buy one of those 650-square-foot cottages,” he says.

CNE will build the first missing-middle housing units from the plan in the Ridgedale neighborhood this year. The four-block area will include a mixture of duplexes, quadraplexes, six-plexes and single-family homes. As CNE continues to build housing in Chattanooga, officials say there will be an ongoing focus on residential buildings that allow missing-middle housing that meets the needs of city residents.