Reading “$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America” both reinforces the critical service provided by NeighborWorks’ network and serves as a stark reminder of how much more is needed.

Reading “$2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America” both reinforces the critical service provided by NeighborWorks’ network and serves as a stark reminder of how much more is needed.

On the one hand, says H. Luke Shaefer, the book’s co-author and keynote speaker at this week’s NeighborWorks symposium in Atlanta, “destitution comparable to those of the poorest people living in places like Haiti or Zimbabwe is rare in the United States due to our public places, private charities and in-kind government benefits.” NeighborWorks’ network of nonprofits plays an integral role in providing the safety net that no longer can be expected from government alone.

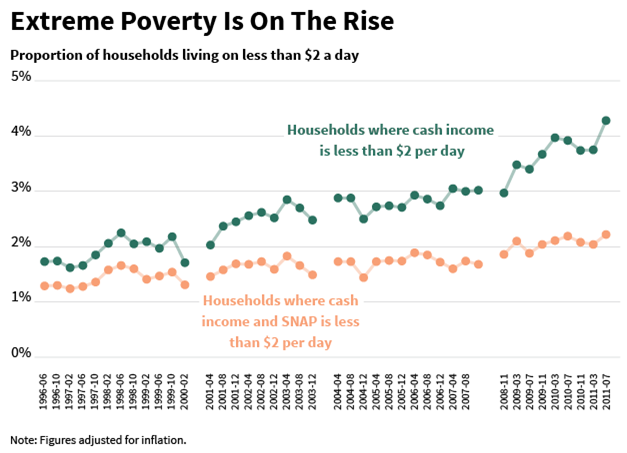

On the other hand, Shaefer documents with genuine heart the shockingly large number of American families who are surviving on cash incomes of no more than $2 per person per day in any given month. In early 2011, the book documents, 1.5 million households with roughly 3 million children fit into this category. That’s about one out of every 25 families with children in America.

“A look into the Census Bureau statistics reveals that all across America, there are thousands of struggling cities and towns,” say Shaefer and his co-author, Kathryn Edin. “Many of these places, and the rural regions where they are located, are hidden from view in pockets of the country that other Americans have largely forgotten. And yet they are America, as much as any other place in the country.”

____________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Family Services Inc. focuses on three counties in the South Carolina “Lowcountry,” some of which are very remote. “We decided we needed to go to them instead of having them come to us,” say Jenna Johnson, marketing and development director. It partnered with two other organizations (United Way and Goodwill Industries) to open a one-stop “Prosperity Center” in two of those very rural locations, featuring financial education, workforce development and basic needs assistance. Likewise, Hope Enterprise Corp. and Credit Union, which operates in an area Shaefer discusses at length in his book, the heart of the Mississippi Delta, has made it a point to locate branches in towns with fewer than 2,500 residents.

Family Services Inc. focuses on three counties in the South Carolina “Lowcountry,” some of which are very remote. “We decided we needed to go to them instead of having them come to us,” say Jenna Johnson, marketing and development director. It partnered with two other organizations (United Way and Goodwill Industries) to open a one-stop “Prosperity Center” in two of those very rural locations, featuring financial education, workforce development and basic needs assistance. Likewise, Hope Enterprise Corp. and Credit Union, which operates in an area Shaefer discusses at length in his book, the heart of the Mississippi Delta, has made it a point to locate branches in towns with fewer than 2,500 residents.Shaefer and Edin outline several principles and initiatives they beleive would go a long way toward alleviating the inequity of this underclass of America:

- Any response to $2-a-day poverty must be in line with America’s values. The authors document the growth in deep poverty following the 1996 welfare reform, which provided a powerful boost for the working poor, but disenfranchised those who can’t find or keep a job. David Ellwood, whose writings inspired former President Bill Clinton’s reform measures, recognized that Americans seem to viscerally hate the concept of “welfare.” Thus, he proposed that for those unable to find work when a time limit for assistance expired, a public, minimum-wage job would be provided. Unfortunately, that part of his proposal fell by the wayside by the time it passed Congress (and, in fact, caused him to resign his position at the Department of Health and Human Services). As a result, the number of children living in $2-a-day poverty more than doubled in just a decade and a half.

- The poor should be integrated into society, not isolated from it. It is critical that we continue to invest in revitalizing disadvantaged neighborhoods to make them ‘higher-opportunity places’ while also offering lower-income residents the option of moving into those that already are,” agrees Tom Deyo, NeighborWorks’ vice president of national real estate programs.

- Everyone deserves the opportunity to work. “It is typically the opportunity to work that is lacking, not the will,” documents Shaefer through the stories of the 18 families followed for the book. The problem is that the desperately poor tend to have a host of related problems and needs and thus not only are at the end of the hiring queue but are set up for failure unless they receive wraparound support. And thus there is a powerful role to play for nonprofits like NeighborWorks members.

Take Arizona’s Pimavera Foundation, for example. It recognized that to get out of homelessness, employment is critical. Many of the residents it serves rely on temporary day labor both for income and as a bridge to a more permanent solution—not to mention the self-esteem it builds. However, day-labor contractors are not always the most ethical employers. As Shaefer’s book documents, wage theft is commonplace and day laborers are frequently denied breaks, forced to work longer than agreed, or even threatened or assaulted by employers. The nonprofit filed a lawsuit against the perpetrators and launched Primavera Works. The alternative staffing service provides temporary and temp-to-hire workers to residential, business and governmental customers, employing persons with significant barriers to employment. They receive job-readiness and employment-retention training; one-to-one employment coaching; assistance with housing, work supplies, clothing and transportation; and, of course, work for which they not only earn a fair wage but also builds experience and self-esteem.

- Parents should be able to raise their children in a safe, healthy place of their own. NeighborWorks members won’t be surprised by conclusions such as this in Shaefer’s book: “Today, there is no state in the nation in which a family that is supported by a full-time, minimum-wage worker can afford a two-bedroom apartment at fair-market rent without being “cost-burdened” (spending more than 30 percent of its income on housing). In addition to development of affordable housing, financial education and workforce development programs like Primavera’s, nonprofits often work hard to avoid the evictions that lead to a continual change of address for the $2-a-day poor. “What Rae [one of the book’s protagonists] wants – more than anything in the world – is two things. First, she wants a job she can throw herself into, fully and completely. Like [the rest of the individuals documented], she is happiest when she is working,” Shaefer and Edin write. “Second, she wants a little place for herself and her daughter, a place where they can be together, play together, be a family: a place where they can drown out the noise around them.”

- Not every parent will be able to work, or work all the time, but their well-being should still be ensured. That means a functioning cash safety net to catch people when they fall. “We’ve made people jump through hoop after hoop (to get assistance)—all based on the not-so-subtle presumption that they are lazy or immoral, intent on trying to put something over on the system," Shaefer and Edin write. "As a nation, the question we have to ask ourselves is, ‘Whose side are we on?’ Can our desire for, and sense of, community induce those of us with resources to come alongside the extremely poor among us in a more supportive, and ultimately more effective, way?”

And then there is 11-year-old Tabitha and her classmates in the Mississippi Delta. A Teach for America instructor took them on a once-in-a-lifetime trip to Washington, DC—but it was bittersweet.

As they boarded the plane home, she says, “everyone was so mad at Mr. Patten ‘cuz we was, like, ‘You take us all the way out here, you show us this, and then you take us back to the Delta where there’s nothing!” Once they were back home, it was back to “waking up everyday, not having enough food, sleeping with seven of us, it was like, seven, eight of us in the bed with the rest of them on the floor. And sometimes as week or two we go without lights, and then just the feeling, like, you’re just starving.”

The moral of the story: Our work is long-term, and the Tabithas of the world deserve our constancy and consistency.