Within NeighborWorks and among professionals who look to us for training and support, the debate rages about the extent to which we should be defined as “housers.” After all, providing housing that is affordable to those with lower incomes was NeighborWorks’ founding “reason to be,” and is the basis of continued funding by the U.S. Congress.

However, at “Creating Opportunity through Collaboration,” the Wednesday symposium at the Atlanta NeighborWorks Training Institute, the case was compellingly made that to truly serve people and the places they call their community, housing should be seen as a “portal” through which other opportunities can be created for a more holistic approach to quality of life.

American jobs and the affordable housing challenge

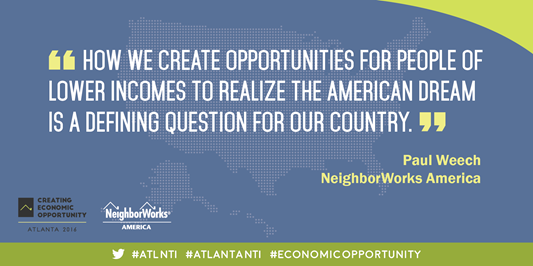

Kicking the day off was H. Luke Shaefer, co-author of “$2 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America.” I’ve already covered the book in detail in a previous blog post, but an overriding “take-away” from Schaefer’s talk, highlighted by NeighborWorks CEO Paul Weech at the end of the day, is worth extra emphasis: Sustainable employment should be seen by “housers” as another—increasingly necessary—means of assuring healthy, affordable shelter.

H. Luke Shaefer

One of the first lines of defense when the very poor become have no safety net is to “double up”—with family or friends. Paul Heckewelder, one man described in Shaefer’s book, opened up his dilapidated home—his only asset—to a total about 20 family members. Although once an owner of several pizza shops, he was forced to close them in the midst of the Great Recession. Unfortunately, the ubiquitous practice of doubling up too frequently results in physical health problems due to overcrowding and psychological trauma due to abuse of various types—at the hands of those same friends and relatives.

“Is the affordable housing crisis in large part a jobs crisis?” Shaefer asked the audience to consider. “Earnings at the bottom (levels of society) have fallen more than rents have risen. Without a livable, reliable income, a stable, healthy place to call home and raise children is almost impossible.”

Shaefer pointed out that like having a home, employment provides holistic benefits: “Having a job is a mental health intervention. It restores a sense of belonging, of order, of dignity.” Even more important than the wage itself, he added, is stability—reliable, sufficient hours and safe conditions.

Mapping a path to increased economic security

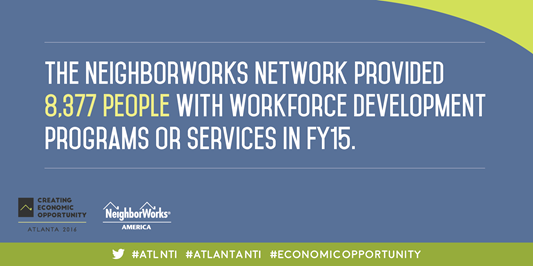

In the panel discussion that followed, the talk focused in part on collaboration in the workforce development space. Robert Doar, the Morgridge fellow in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute, suggested that organizations target the local offices of programs such as TANF and Medicaid, rather than regarding them as federal monoliths. Schaefer discussed how to involve businesses as partners, citing a success story in Michigan. Gov. Rick Snyder awarded a $5,000 subsidy to employers for each structurally unemployed worker hired and retained for at least a year. Wraparound services are offered to support participating employees.

“Many of these people are from communities of color,” said Nathaniel Smith, founder of the Partnership for Southern Equity. “These are the faces of the future of America, and they are the untapped resource we need to remain competitive.”

Referring to the current “hot” debate about investing in places vs. encouraging the mobility of people, Smith called on professionals in the room to remember that “places are important but so are people. We need public policy changes to ensure that when a neighborhood gentrifies, the original people have the opportunity to remain during the good times, not just the hard times. Otherwise, we’re just pushing people from one bad place to another. It requires a regional consciousness."

“In a real sense, all life is inter-related. All men are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be...This is the inter-related structure of reality.” Martin Luther King Jr, Letter from the Birmingham Jail

Community Commitment: Housing and Community Development as a Foundation for Opportunity

“Once you start collaborating, there’s really nothing you can’t do.” Those were the inspirational words of Stefanie Shull, director of The Neighborhood Developers’ CONNECT program in Chelsea, MA.

"To me, economic opportunity means..."

Shull described the community TND serves as a large hub of mostly Central American immigrants, with nearly half of the residents foreign-born. A quarter are under the poverty line, many don’t have their GED and they must cope with the highest rate of violent crime in Massachusetts.

“We started in housing, but we have to serve the people,” recalled Shull. “It was clear housing wasn’t enough. Our residents have complicated lives, and a crisis in one sector can set them back in all of the others.”

So, TND looked for partners, including a community college and a credit union. The result is CONNECT: a one-stop center with services co-located in one building provided by TND. One of the chief lessons learned? “Co-location is not enough. It’s about mindfully nurtured relationships, structured communications, smart use of data to guide decision-making…..and, muffins at meetings!"

Nadia Villagran, director of operations and communications for Coachella Valley Housing Coalition in Southern California, said her organization took the same philosophy, allowing residents’ needs to guide its services and priorities—which led the organization to a network of cross-sector collaborations. It had long provided housing to a largely rural, migrant population, but the residents said they needed child care. So Coachella partnered with a school that had received funds from the state Department of Education for a such a center, but didn’t have the space. Coachella did. Seeing that Coachella had listened, the residents said they needed more-immediate access to health care. A medical center followed.

“We build space,” said Villagran. “That’s what we are good at; we get others to use that space to serve our residents.”

The twist that Ernest Coney Jr., CEO of the CDC of Tampa, FL, brought to the same challenge was the use of technology. Coney has a health care background, and had seen how technology could be used to network facilities so that patients didn’t have to repeat their histories everywhere they went. The same problem plagued resident services in Tampa, so his organization created an Economic Opportunity Center that networked 18 different service providers, allowing each to share client information with the other. The CDC of Tampa serves as both a provider and the “community quarterback” for the center.

Start with what you have: leveraging existing coalitions to improve outcomes

“We are building solutions for tens of hundreds, when we need them for tens of hundreds of thousands.” Geoffrey Canada, founder, Harlem Children’s Zone

Since resources are limited, and the need for scale is so pressing, collective impact is essential. However, “achieving collective impact is incredibly messy and difficult,” said Jeff Edmondson, managing director of StriveTogether, a national cradle-to-career initiative. “That’s why we are so big on what we call ‘failing forward.’ We can’t just ask for more, we have to do better, together, with what we’ve got.”

Edmondson listed four “must-haves” to progress past collaboration to achieve collective impact:

1) Convene around outcomes, not programs.

2) Use data to improve, not prove.

3) View collaboration not as something that is in addition to what you do, but what you do.

4) Advocate for what works, not ideas.

He concluded with a few lessons learned in the course of his organization’s work:

1) Find your “true north”; what are the outcomes that matter most?

2) Use data as a flashlight to inform action, not as a hammer. Remember, the goal is continuous improvement.

3) Share the accountability, but differentiate the responsibility.

Inspired? Attend the next symposium in Los Angeles, which will look at some of the same issues through the lens of race and culture.