Bankruptcies….Closed businesses…Declining jobs…Run-down neighborhoods. It sounds like Detroit, but it’s a scenario that has been repeated over the last decades across the country. And each city must find its own formula to fight its way back. Orange, New Jersey, has found a winning approach that leverages arts and culture to grow a more vibrant economy. It’s just one example of “creative placemaking” that is proving successful in cities and towns across the country.

In fact, the Bohemian Index shows that both people and jobs are attracted to natural and cultural amenities. A new study in the Journal of Regional Studies, based on the index, concludes that such amenities increase the attraction of places for both people and industries. And that’s why this year, NeighborWorks is undertaking a planning process to further explore how arts, culture, creativity and placemaking can contribute to vibrant communities. Through its NWArts project, NeighborWorks will identify ways to leverage its unique strengths to support the network and the broader field when adopting and implementing creative practices.

“Arts-based strategies have long occupied a central role in community development,” says Ascala Sisk, Senior Vice President for Community Initiatives at NeighborWorks America. “Through this process, we seek to thoughtfully and systematically explore ways that arts and culture can advance inclusive and equitable community development.”

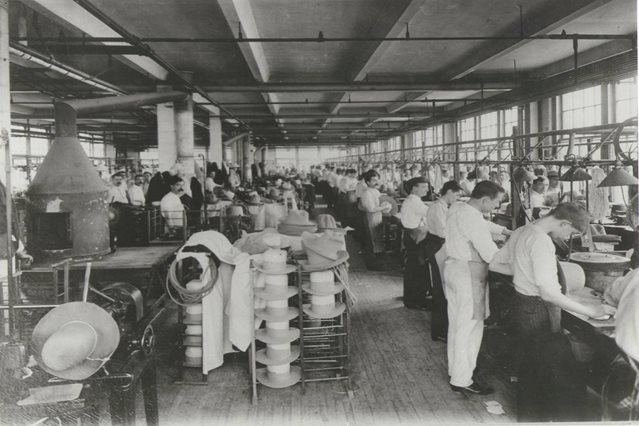

The problem in Orange

“It wasn’t just economic forces,” notes Christine Jackson, Director of Communications for Housing and Neighborhood Development Services, known as HANDS. “There were cultural shifts as well. It just wasn’t popular to wear hats anymore and demand dwindled. Communities must be flexible enough to transition along with those kinds of changes.”

The arts were increasingly viewed as an effective platform for all sorts of revival strategies, and along with that new thought came new sources of funding. Another fact that made an arts-oriented strategy attractive to Orange was its proximity to New York City and a ready population of artists who increasingly could not afford Brooklyn or even Queens. The district’s first “toe in the water” came in 2001 with a first of an annual music and poetry festival. In 2003, HANDS decided to learn more about what residents wanted for the neighborhood. In partnership with Seton Hall University, HANDS conducted a daylong visioning and needs-assessment forum attended by more than 600 stakeholders. Contemporary culture emerged as a desired touchstone.

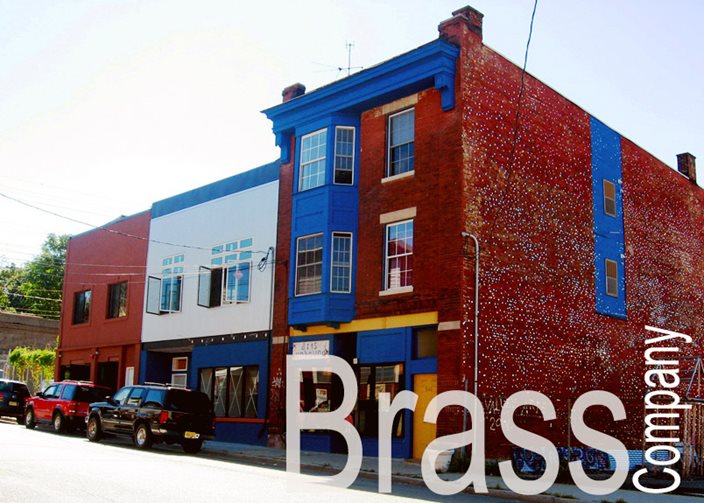

Co-opting vacant buildings

Because these old buildings began as factories, a particular challenge has been cleaning up after the environmental contamination and securing approval from the Environmental Protection Agency. This process was managed by HANDS to "unlock" the property's potential.

“It’s very costly to remediate property that might have asbestos, soil contamination and lead-based paint or building materials, so it's not always cheaper to just tear it all down and do it over again,” notes Jackson. “An important thing to keep in mind is that you don't want to lose the historical legacy, but you do need the funds, fortitude and tenacity to get the job done right. It’s highly regulated so you must be sure to follow the steps and know the right questions to ask and what grants are available. Hiring an experienced consultant is usually necessary.”

Introducing ValleyArts

Youth programming

- After-school arts programming with the local elementary schools, taught by professional working artists. This program is funded by a grant from the U.S. Office of Academic Improvement.

- Spoken word and poetry events for high school students in collaboration with a local professional theater company.

- Filmmaking workshops in partnership with a local nonprofit, high school and university, in which the students work create five-minute films that are judged by industry professionals and presented at to the public.

- The artfullbean café, featuring fair-trade coffee and locally made arts and crafts. A nice touch is the reclaimed wood coffee bar–featuring 127-year old pieces of wood donated from a resident's home.

- ValleyD Radio, a community-based internet radio station offering eclectic programming 24/7/365.

- A community art gallery.

- Social enterpries, such as a community theater.

- “Makers + Movers,” a membership organization for entrepreneurs, with the goal of fueling economic opportunities.

- Business incubator space, with offices for start-ups doing work in and around the district. Among the new businesses these incentive have helped attract are a manufacturer of hand cream that caters to men and a clothier that makes custom-tailored dress shirts and leather jackets.

“One of our most important lessons learned is how important it is to partner,” says Jackson. “We are a community-revitalization organization with a principle focus on repurposing deteriorating, vacant properties. We realy on partners to provide arts programming, events education and business support.”

Lessons for all

The National Endowment for the Arts offers six lessons for those interested in creating and managing art, cultural and entertainment (ACE) districts:

Be local: ACE districts should reflect the history and culture of their locations. No single solution or recipe for success exists. While it is helpful to study how others have proceeded, it is dangerous and ill-advised to follow their same path, since the political, economic and social environments all reflect different realities and constraints.

Do your homework: ACE visionaries, builders and managers should analyze their regional arts ecology to determine whether they are better off supporting existing arts activity or building a district from scratch. However, studies have shown it is more strategic to leverage already fertile grounds rather than pursuing a top-down strategy that just shuffles arts activity to new hubs. A big part of this process is not just looking at physical places, but also understanding the needs of the artists and creators.

Connect the dots: ACE leaders should develop integrated solutions that build capacity. Focusing purely on arts programming and marketing keeps the district isolated in a silo. Builders and managers should think about connections in the broad sense: For example, is the district physically connected to the city’s infrastructure? Is it politically connected to other citywide initiatives?

Invest in partnerships: ACE leaders should identify stakeholders that can contribute political, financial, regulatory and cultural resources and expertise. It is wise to create partnerships from a diverse set of interests—whether it is well-funded foundations, entrenched neighborhood organizations, nearby universities and colleges, invested businesses, community advocates, associated public policy staffers or others.

Be adaptive, flexible and nimble: Visions and plans are wonderful and help set a longer course, but they need to accommodate the realistic and day-to-day realities of building and managing arts districts. Comprehensive and ongoing SWOT (strength, weaknesses, opportunity and threats) analyses help stakeholders determine how to keep improving. Whether the district is a new, exciting concept or an established, maturing one, each must adapt to changing city priorities, new leadership and periods of financial distress.

Be thoughtful about management structure: What financial and management model to adopt is a critical decision. For example, many arts district initiatives are underfunded. However, it is critical to not focus so much on fundraising mission drift occurs or the director is unable to allocate sufficient time to operations. Many ways exist to finance arts districts, including local taxation, state tax incentives, philanthropic or corporate investments, public façade improvement programs and historic preservation grants. A variety of ways also exist to manage districts, including a public agency, a nonprofit organization, volunteers or a private, commercial enterprise.

“To me, the most exciting potential for this approach is recapturing the narrative of what makes a place worthy of investment,” writes Seth Beattie, arts and culture program officer for The Kresge Foundation. “Exploring a place’s history, celebrating its culture and helping people envision an achievable future—that is a place where artists can have immense impact.”