|

| Ta-Nehisi Coates and his 15-year-old son, Samori |

di·ver·si·ty

dəˈvərsədē,dīˈvərsədē/

noun: diversity

the state of being diverse; variety.

synonyms: variety, assortment, mixture, mélange, multiplicity

One of NeighborWorks CEO Paul Weech’s actions during his first year of which he is most proud is an initiative we all call “REDI” for short—a short word into which a lot is packed: race, ethnicity, diversity and inclusion.

“Race” and “diversity” are bandied about a lot—so often that they have become a kind of shorthand for anything, everything…and too often, nothing. As Anna Holmes asked late last year in The New York Times magazine, “How does a word become so muddled that it loses much of its meaning? How does it go from communicating something idealistic to something cynical and suspect? If that word is ‘diversity,’ the answer is: through a combination of overuse, imprecision, inertia and self-serving intentions…It has become both euphemism and cliché, a convenient shorthand that gestures at inclusivity and representation without actually taking them seriously.”

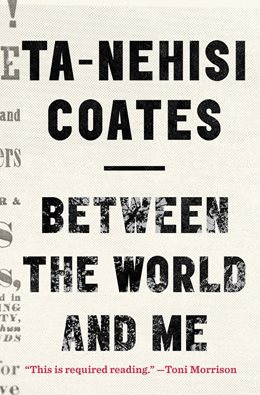

Even the word “race” can be used to conveniently obscure some of the deeper currents at work. In his much-acclaimed letter to his son, “Between the World and Me,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, “Race is the child of racism, not the father. And the process of naming ‘the people’ has never been a matter of genealogy and physiognomy so much as one of hierarchy. Difference in hue and hair is old. But the belief in the preeminence of hue and hair, the notion that these factors can correctly organize a society and that they signify deeper attributes, which are indelible—this is the new idea at the heart of these new people who have been brought up, hopelessly, tragically, deceitfully to believe they are white.”

The words “equity” and “inclusion” come much closer, perhaps, to universal yet substantive concepts around which we all can rally. That does not mean, however, that we must not first, as a society, in the workplace and in local communities own the fact that many of us grew up, and currently live, in parallel worlds that dictate entirely different lenses through which we see life.

In a workshop on “Privilege, Power, Prejudice” at the last NeighborWorks Training Institute, a white woman commented with very good intentions that although she knows blacks still struggle with many challenges, the United States has come far and is much better than many other countries. Further progress will come, she said; we just need to be patient. A black man, another participant, answered swiftly: “You are not a black man, with a black son. You don’t have to worry that if he attracts attention on the street, he’ll get picked up for no reason and harassed. We don’t have more time. It’s been too long already. It has to change now.” [Note: the workshop is offered again at the Atlanta NTI; it is full, as usual—which is a good sign. Be sure to attend the May 4 symposium totally devoted to race, culture and opportunity, and also consider these courses: "Building a More Inclusive Organization and Board of Directors" (ML242) and "Leadership Development in Communities of Color" (ML245).]

This difference in views is the theme behind the title of the book, “Between the World and Me.” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes about growing up in West Baltimore, the home of Freddie Gray, the young black man whose death while in police custody helped spark the uprising that gained national attention. Based on what he saw on TV, he knew there was a world other than his own, one where he didn’t have to be on guard and pretend he was tough all the time, which he called “the Dream.”

“Outsiders” coming into his neighborhood, including police officers who live in better-off, or whiter, neighborhoods, would likely see—through their own, personal lenses—swaggery, hostile teens looking for trouble. But that’s not the reality Coates lived and experienced. The swagger hid something else.

“I think back on those boys now and all I see is fear; all I see is them girding themselves against the ghosts of the bad old days when the Mississippi mob gathered round their grandfathers so that the branches of the black body might be torched, then cut away. The fear lived on in the extravagant boys of my neighborhood, in their large rings and medallions, their big puffy coats and full-length, full-collared leathers, which was their armor against their world. The fear was in their practiced bop, their slouching denim, their big T-shirts, the calculated angle of their baseball caps, a catalog of behavior and garments enlisted to inspire the belief that they were in firm possession of everything they desired. I heard the fear in the first music I ever knew, the music that pumped from boom boxes full of grand boast and bluster. The boys who stood out on Garrison and Liberty up on Park Heights loved this music because it told them, against all evidence and odds, that they were masters of their own lives, their own streets, and their own bodies.

“I think back on those boys now and all I see is fear; all I see is them girding themselves against the ghosts of the bad old days when the Mississippi mob gathered round their grandfathers so that the branches of the black body might be torched, then cut away. The fear lived on in the extravagant boys of my neighborhood, in their large rings and medallions, their big puffy coats and full-length, full-collared leathers, which was their armor against their world. The fear was in their practiced bop, their slouching denim, their big T-shirts, the calculated angle of their baseball caps, a catalog of behavior and garments enlisted to inspire the belief that they were in firm possession of everything they desired. I heard the fear in the first music I ever knew, the music that pumped from boom boxes full of grand boast and bluster. The boys who stood out on Garrison and Liberty up on Park Heights loved this music because it told them, against all evidence and odds, that they were masters of their own lives, their own streets, and their own bodies. “To be black in the Baltimore of my youth was to be naked before the elements of the world, before all the guns, fists, knives, crack, rape and disease. The nakedness is … the predictable upshot of people forced for centuries to live under fear.”

Kwame Rose, a social activist and artist best known for holding media accountable during the Baltimore unrest, explained the consequences of these different world views in a Mashable article on the recent spate of police officer shootings of young blacks:

“It is not that the victims didn't understand what the police represented. Mostly, these conflicts began when authorities didn't understand the people they were meant to protect. The white officers could never understand why Freddie Gray ran away from them in fear of his life. There isn't a manual that can teach outsiders how to police a neighborhood he or she doesn't understand.

“The white officer who initiated contact with Freddie Gray could never know what it was like to be raised in such an environment. Oddly enough, in a city where black unemployment is rampant and more than half of black children live in low-income households, the police force is overwhelmingly made up of white men, who aren't from Baltimore.”

A gap between worlds—whether they be defined by the color of your skin, the culture with which you identify, your sexual orientation, the income of your neighborhood or, more likely, a stew of these dynamics and others—accounts for many of the clashes that tear us apart, no matter what the setting. In the context of policing, one answer is to recruit and train officers from the communities they are charged with protecting.

However, in the workplace, community space, etc., it must actually mean the opposite—rising above a quota or a sensitivity workshop to find, as Holmes writes, “a place from which a more integrated, textured world is brought into being.” And that can be so much more than an obligation; if done right, it can be downright exciting.

Note: I serve as a member of the REDI committee of NeighborWorks employees, and I am happy to report that so far it is just that--a refreshingly candid (even brutal) exchange focused on transformation, not rote exercise.