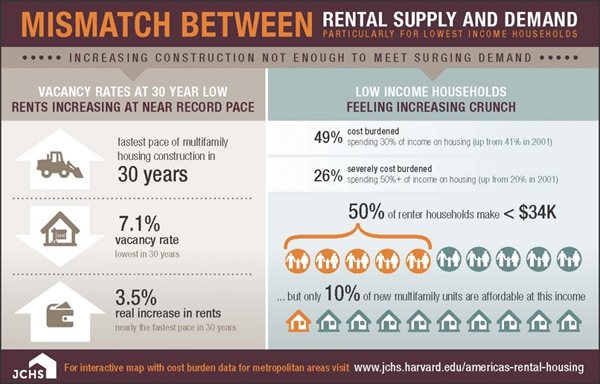

This infographic from the Joint Center for Housing Studies’ “America’s Rental Housing” report, issued in December, tells a story within a story. The number of renters is surging in unprecedented numbers—the largest gain in any 10-year period on record. In response, new rental construction is ramping up.

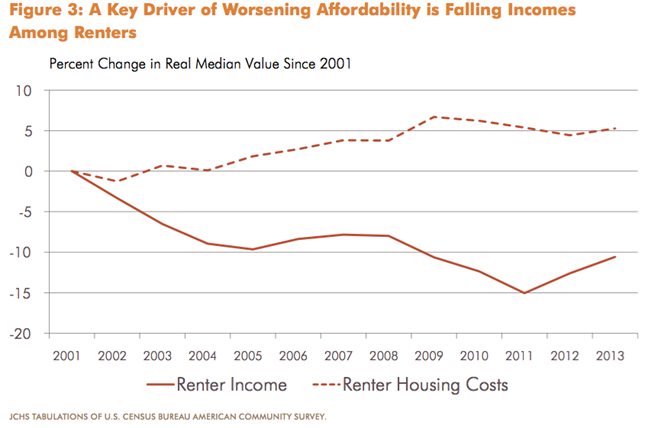

So the market is “working,” right? Wrong. Much of this new housing is located in large properties in urban areas and intended for upper-income renters. According to the JCHS, the number of low-cost rental units ($400 a month or lower) increased just 10 percent from 2003 to 2013, while low-income renter households rose by 40 percent. And it’s not just the lowest-income segments who are being squeezed. The net gain in moderately priced units ($400-$799 a month) was 12 percent, compared to a 31 percent increase in renter households that could afford only this price range.

One of the trends driving the crisis is a loss of existing affordable rental properties. Because housing options with such low rents are particularly vulnerable to deterioration, demolition and replacement with market-rate units, 11 percent were permanently lost from the stock by 2013. Unless we find a way to maintain as well as increase the supply of rental housing that is affordable to both low- and moderate-income individuals and families, the United States will experience a growing crisis that could ripple through the economy (not to mention disenfranchise a significant number of people).

“The consequence of severe renter cost burdens are far-reaching,” the JCHS report states. “In 2014, households in the lowest expenditure quartile who paid more than half their incomes for housing spent 38 percent less on food and 55 percent less on health care. Those of working age also put 42 percent less toward retirement savings than otherwise similar renters living in affordable housing.”

Frances Ferguson, director of real estate enterprise strategies for NeighborWorks, agrees: “We need to use more funds to target the preservation of existing rental housing, with a special focus on locations near transit and successful schools. Fair housing is about giving people of all incomes choices. If there is no supply, there is no choice. And, if there is no choice, there is no diversity.”

Leveraging private equity

So…In a time of shrinking government and philanthropic resources, what can be done to facilitate and finance preservation of existing affordable rental housing? One emerging solution is the topic of a new paper published jointly by the Urban Land Institute and NeighborWorks America. Titled “Preserving Multifamily Workforce and Affordable Housing: New Approaches for Investing in a Vital National Asset,” the paper profiles 16 examples of the use of “social impact investing” to finance this critical work, while still delivering a return to equity investors of 6-12 percent.

So…In a time of shrinking government and philanthropic resources, what can be done to facilitate and finance preservation of existing affordable rental housing? One emerging solution is the topic of a new paper published jointly by the Urban Land Institute and NeighborWorks America. Titled “Preserving Multifamily Workforce and Affordable Housing: New Approaches for Investing in a Vital National Asset,” the paper profiles 16 examples of the use of “social impact investing” to finance this critical work, while still delivering a return to equity investors of 6-12 percent.

“Current levels of new affordable multifamily development—roughly 100,000 annually—will replace only about half of what is at risk of loss in the coming years and will fall far short of meeting rising demand. It is no exaggeration to say that, absent unforeseen policy interventions, much of the current stock of multifamily workforce and affordable housing will be lost for good,” writes ULI Executive Director Stockton Williams. “But these [financing] approaches, led principally by the private sector and nonprofit organizations, are demonstrating that in fact a market opportunity exists to at least partly meet this pressing social need.”

Although there also is a need to develop an increased supply of workforce rental housing, the paper concludes that “investing in the existing housing infrastructure for lower- and middle-income renters is in fact a much higher-yielding financial and social investment for the country than building new apartments for this group.” According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, preservation costs 30–50 percent less than developing new units.

The types of social-impact investing profiled in the ULI/NeighborWorks report are:

The types of social-impact investing profiled in the ULI/NeighborWorks report are:

■ Below-market debt funds, through which entities established by partnerships of private, public and philanthropic organizations provide affordable housing developers with low-cost loans, paying below-market interest rates to senior lenders.

■ Private equity vehicles, in which private capital is used to acquire and rehabilitate multifamily properties while delivering a range of returns to equity investors. The paper focuses only on arrangements that include a commitment to maintaining affordability for current middle- and lower-income renters—typically those earning 80-100 percent of the area median income.

■ Real estate investment trusts (REITs), in which a mechanism originally established to raise capital for other types of projects is used to develop and preserve affordable rental units, generating a range of returns.

“While the aggregate amount of additional capital these financing approaches have made available to date still is relatively small… most of it has emerged or scaled significantly just in the past several years,” the paper states. “It represents a significant trend and arguably a best option for alleviating an important aspect of our country’s worsening affordable housing crisis.”

Cautions to keep in mind

There are a few caveats, however. For example:

■ These mechanisms won’t help everyone. All of these approaches must find the right balance between the demands of equity investors and their commitment to serve lower- and middle-income renters. Most of the approaches effectively recruit private equity investors to accept returns that are lower than the typical mid-high teens, but higher than returns on debt. They are able to achieve this goal by focusing mainly on renters earning 80-100 percent of area median income, the “upper half” of the “lower and middle income” category. (One exception is below-market debt funds, which may be able to serve households earning as little as 60 percent of their area’s median income or even less, because their “capital stack” includes public and philanthropic funds that require no or low financial returns.)

“Most of the very neediest residents won’t be covered by these financing mechanisms,” agrees Ferguson. “But these tactics could significantly reduce the loss of older, well-located properties and bend the cost curve over time by avoiding high-end redevelopment.”

■ Banks may lose CRA incentives. Banks may not receive full CRA (Community Reinvestment Act) “credit” for financing a property that does not exclusively serve low-income households or that does not have some sort of federal subsidy.

“Many cities are seeing a dramatic re-urbanization,” notes Ferguson. “And that is imposing huge inflationary pressures on land economics at the same time that wages are stagnating. I hope those who read this post will download and read the full paper. Perhaps they will identify funds in their area with which they could work. At NeighborWorks America, we’re already discussing how we might help attract more capital to provide equity for nonprofit acquisition and preserve long-term affordability.”