At 18, most young people would be hard-pressed to make it on their own without the support of a nurturing family. No longer children — yet not fully adults — many are blessed with considerable financial and emotional backing from caring adults while they pursue college or a career. Because this support is available, these youths have a good chance of transitioning to young adulthood and eventual independence successfully.

At 18, most young people would be hard-pressed to make it on their own without the support of a nurturing family. No longer children — yet not fully adults — many are blessed with considerable financial and emotional backing from caring adults while they pursue college or a career. Because this support is available, these youths have a good chance of transitioning to young adulthood and eventual independence successfully.

However, without a stable home environment and healthy relationships with adults, the outcome can be starkly different. This is the unfortunate reality faced by some 23,000 young people who exit, or “age out,” of America’s foster-care system every year at a vulnerable age. While most states offer support for youth in foster care up to the age of 21, the majority opt to exit the system after turning 18 — when they are legally considered adults. Like most 18-year-olds, they’re financially ill-prepared to be fully independent. Their challenges are exacerbated by histories of abuse, abandonment and neglect. Left to their own devices after aging out, and with few resources or marketable skills, many get into trouble.

A grim outlook

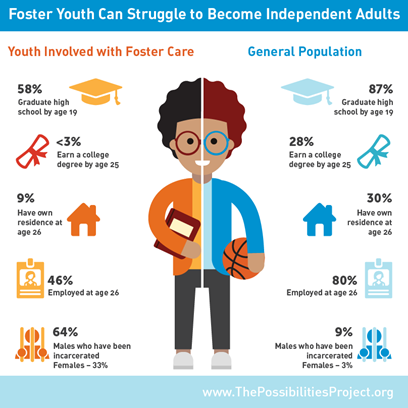

The statistics are bleak. Within two years of aging out of the foster care system:- 1 in 4 young people will be incarcerated.

- 1 in 5 will be homeless.

- Fewer than 1 in 6 will graduate from high school.

- 71 percent of the girls will become pregnant.

Crafting an innovative solution

Helping to guide these vulnerable young people towards a safe and stable adulthood is a smart investment. According to the Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative (of the Annie E. Casey Foundation), the price of the status quo amounts to about $300,000 per youth, per year. That’s a total cost of more than $154 million in public assistance for the 500 youth who are aging out in Virginia alone.

In 2015, NeighborWorks member Better Housing Coalition (BHC) partnered with Children’s Home Society of Virginia (CHS), to tackle this complex issue. The executive directors of the two Virginia-based nonprofits—one an affordable-housing developer and the other an adoption agency—met at an after-work social one evening and began to brainstorm on how their organizations’ missions, if combined, might work to improve the lives of vulnerable populations who lacked access to quality, affordable housing.

That discussion morphed into what would become The Possibilities Project (TPP), a multi-pronged program to provide housing and social support to youths aging out of Virginia’s foster-care system. The initial goal was to conduct a two-year research and demonstration project with 10 participants, then make policy recommendations and replicate the program state-wide and even nationally.

The pilot has been a success. In the past two years, TPP has supported 20 young people, as well as others who received temporary emergency services. And TPP won a Best Housing Program award at the 2016 Virginia Governor’s Housing Conference.

“The Possibilities Project is having an early impact,” says Nadine Marsh-Carter, president and CEO of CHS. Two years in, “all of our participants have housing, nearly all have jobs, three-fourths are enrolled in post-secondary education or have completed career training, and they all have access to trusted adult mentors and health care services.”

Evidence-based, trauma-informed support

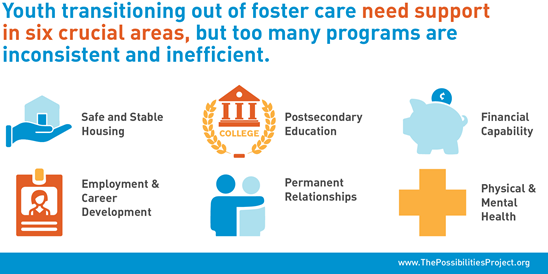

The two organizations needed solid research to back up anecdotal observations. Noting the lack of consistency in support services for these youths across—and sometimes within—states, BHC and CHS commissioned Child Trends to conduct a nationwide survey of extended foster-care services. The results revealed that states commonly fall short in supporting young adults in six key areas: housing, education, employment and career development, financial capability, physical and mental health, and formation of permanent relationships. Furthermore, existing state programs lacked proven records of effectiveness.

The two organizations needed solid research to back up anecdotal observations. Noting the lack of consistency in support services for these youths across—and sometimes within—states, BHC and CHS commissioned Child Trends to conduct a nationwide survey of extended foster-care services. The results revealed that states commonly fall short in supporting young adults in six key areas: housing, education, employment and career development, financial capability, physical and mental health, and formation of permanent relationships. Furthermore, existing state programs lacked proven records of effectiveness.“Housing is fundamental to the short- and long-term success of young adults who lacked stability during their childhoods,” says Greta Harris, BHC’s president and CEO. “The other pieces of success more easily fall into place once a person has a safe and stable place to live.”

Through TPP, participants have access to basic needs like transportation, the internet, a living stipend and life-skills training. BHC provides housing and related support and CHS offers ongoing case management and social services.

TPP’s success is assessed by the level of achievement each participant makes in each of the six support areas. An individual strategy is developed with all of the youths, and as they reach their goals, they transition to living independently.

In March 2016, the first group of TPP participants were welcomed into the program and given keys to fully furnished, shared apartments on BHC’s Winchester Greens campus in North Chesterfield. All participants were assigned a roommate for mutual support, accountability and relationship-building.

One was 20-year-old Michelle (her name has been changed to protect her identity), who had spent her entire life in foster care. Michelle was determined to complete her education and was enrolled at a community college. Despite her determination, she struggled with a learning disability and was failing most of her classes. In addition, her job didn’t pay enough for her to secure decent housing. She was frustrated by her lack of progress in school and stressed about losing public support after turning 21.

Through TPP, Michelle found housing stability, plus financial and emotional support. This allowed her the peace of mind to better focus on her goals. With guidance from her TPP case manager, Michelle determined that her academic track was not her passion. TPP connected Michelle to a mentor who encouraged her interest in fashion design. Soon after, Michelle switched her field of study and transferred to a four-year university. Michelle won a higher-education scholarship provided by BHC, which helped defray tuition costs. A full-time student, Michelle now maintains a slightly better than 3.0 GPA. She also works full time and is expected to graduate in December 2019. She wants to enter graduate school and eventually own her own business.

As of this publication, TPP has “graduated” its first participant and two more are scheduled to make the transition this fall. Having transitioned out of homelessness and helplessness into confident, capable and independent young adults through the support of TPP, all three are leaving the program better prepared to tackle the challenges that lie ahead.

Pioneer program = lessons learned

“The smallest tasks — such as how to do laundry, pay a bill or use a bank account — were foreign to them,” Gregory says. Their traumatic histories also made it difficult for them to establish trusting relationships with adults or fulfill simple responsibilities. “We quickly learned we had to work rapidly yet carefully to assess individual needs, break through their barriers and use a trauma-informed approach to ensure they stay invested in the process.”

Nonprofit program and development staff will be familiar with another challenge: that of raising sustained funding. Funding for TPP relies on donations from corporations, foundations and individual supporters. To date, the two organizations have raised about $750,000 to fund the research, hire staff and implement the program. BHC and CHS are evaluating ways to identify new and ongoing sources of funding for TPP.

Next steps

An integral piece of the TPP puzzle is advocating for policy change on a local, state and national level. To do that, TPP convened a panel of experts in the areas of housing, employment, education, financial capability and physical/mental health. The CEOs of both BHC and CHS sit on the panel, along with academics, government officials and child-welfare advocates. The panel is working to review the research and form practical policy recommendations.Phase two of TPP now is underway, focusing on developing temporary “step-down” support programs and services for TPP graduates as they move forward with their lives. Support will be customized to each individual’s unique needs and might include a living stipend, assistance with finding housing and continued connections to mentors.

One young program participant said of his TPP experience: “[The first night at TPP was] the best night of my life. Now I know there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”