When I first heard NeighborWorks staff refer to our organization as the “corporation” and the residents we ultimately serve as “customers” (rather than, say, “clients”), I bristled a bit. Like many employees at NeighborWorks America and our network members, I was drawn to this organization because it provides vital assistance to those who cannot afford such services on their own. (In fact, I left my former career in corporate America specifically to escape the profit-driven mentality.) Charging for our assistance, and thus treating those who access it as paying customers, seemed in my mind to be a departure from our mission.

However, I’ve since come to realize there is an “in between” kind of business, one that earns income through commercial activity, yes, but does so to advance a social mission. And this type of “sustainable business” could actually be the key to the long-term health and vitality of the mission to which we all are committed. This is the focus of a special winter 2018 supplement of the Stanford Social Innovation Review, presented by NeighborWorks America.

To help network members explore this new space and develop the skills and resources necessary to succeed, NeighborWorks America launched what it called the Sustainable Homeownership Project (SHP) in 2012. Although focused on homeownership-related services, its capacity-building focus and the learnings from it are applicable to many other types of sustainable businesses.

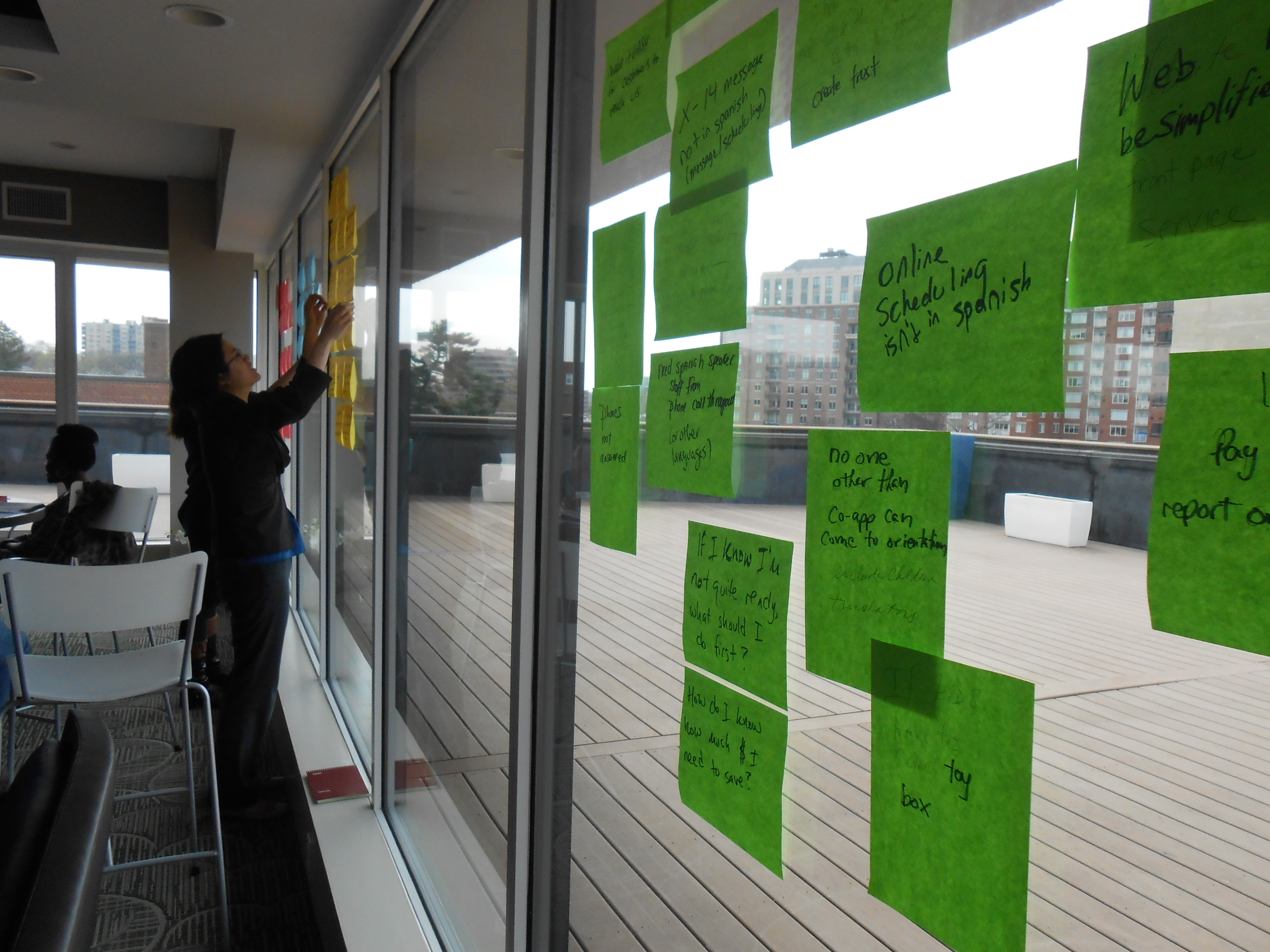

The first phase of SHP was a think tank of sorts, with both external and internal experts working together to discuss the most critical elements of a sustainable-business approach to supporting the homebuying process. In the second phase, 23 NeighborWorks network members joined together to test different approaches. And now, in phase three, 44 member nonprofits are putting the most effective tactics and tools into practice.

The first phase of SHP was a think tank of sorts, with both external and internal experts working together to discuss the most critical elements of a sustainable-business approach to supporting the homebuying process. In the second phase, 23 NeighborWorks network members joined together to test different approaches. And now, in phase three, 44 member nonprofits are putting the most effective tactics and tools into practice.So, just how is this new, sustainable-business model different from the traditional nonprofit approach?

- Reasonable fees (perhaps on a sliding scale depending on income) are charged for services such as homebuyer education. According to Ludy Biddle, Executive Director of NeighborWorks of Western Vermont, fees generate revenue to keep services operating and create a greater perception of value among customers. “This logic stems from the psychology of the sunk-cost effect,” she writes. “People are compelled to use products or services they’ve paid for to avoid feeling they’ve wasted their money.” And, in fact, the number of people attending homebuyer education classes offered by her organization has tripled. Along with moves like launching a realty company, the decision has helped reduce the organization’s reliance on government and philanthropic support from 80 percent to 40 percent.

- Services and products are actively marketed, instead of relying primarily on word of mouth. “Many nonprofits were created to provide services that they and their funders consider to be essential,” writes William Woodwell Jr. in the supplement. “As a result, they may tend to wait for people to come to them. It’s a philosophy of ‘if you build it, they will come.’ But social enterprises focus on how to find customers and personalize the services and products they offer.” For example, NeighborWorks HomeOwnership Center in Utica, New York, launched a “Let’s get you out of mom’s basement” advertising campaign to attract millennial homebuyers.

- Technology is harnessed to identify new customers and keep them. In the SHP project, NeighborWorks America helped customize an online “tech suite” that potential customers can access via laptop, tablet or smartphone to sign up for classes and financial coaching, schedule appointments, upload documents and track their progress toward buying a home. The same program allows user organizations to log all contacts with customers for use in planning support and better understanding market dynamics. “Once a customer is in the system, it provides tools like automated reminders to help us stay in contact,” explains Dawn Lee, Executive Director of Neighborhood Housing Services of the Inland Empire. “In the past, significant numbers of people would drop away for various reasons.”

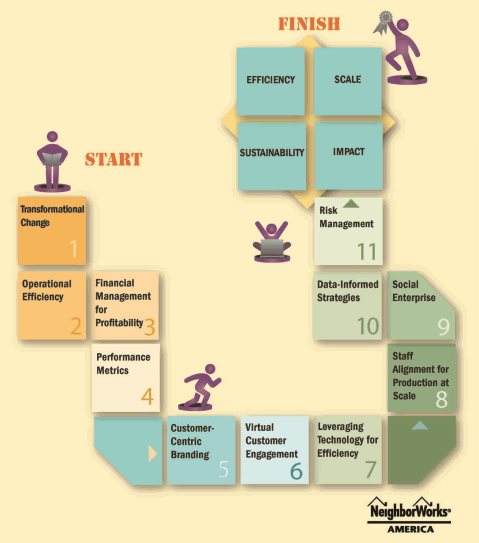

- Hard data are used to drive decisions. To measure outcomes, SHP participants use the same tech suite to track a set of performance indicators called the “Transformative 10,” allowing assessment of efficiency (average cost per customer), scale (number of new leads and customers served), sustainability (ratio of earned versus donated revenue) and social impact (number of new homeowners).

However, transitioning to a sustainable business model brings challenges with it. Chief among them is the necessary culture change. “On top of the challenges posed by any change, transitioning to social enterprise requires staff and leaders to navigate the line between working toward a social cause and operating like a business,” writes Rachel Mosher-Williams, Senior Director of Learning and Impact at Community Wealth Partners. “For many organizations, staff members misunderstand or distrust the business principles that drive it; the focus on generating revenue, for example, may seem to contradict a mission of service.”

Elyse Pitts, Director of Innovation for the Housing Development Fund in Stamford, Connecticut, says the hardest part for her employees was a fear that the reliance on technology would reduce the human contact that is still so important.

Elyse Pitts, Director of Innovation for the Housing Development Fund in Stamford, Connecticut, says the hardest part for her employees was a fear that the reliance on technology would reduce the human contact that is still so important.“But in actuality, technology supports our process; it doesn’t drive it,” she counters. “It allows us to spend a lot more time with the people we are most suited to serve–those who are18 months or less away from being able to buy a home. Individuals or couples who are a longer way off, or for whom renting is simply a better choice, now can be referred more quickly to organizations set up to address their needs.”

The tech suite helps by producing hard data—for example, proof that 50 percent of the time spent with customers before SHP didn’t evolve into a home purchase. “The numbers speak for themselves,” she says. “Of course, it takes time. It’s not like one meeting will get everyone saying, ‘yeah, you’re right.’ And there may be some people who will never get there and insist on the old way of working. Those individuals generally decide to transition out of the organization.”

Other critical steps that determine success include:

- Maintaining relationships with current and potential partners in the market. While forging a competitive advantage is important, so are relationships with individuals and organizations working toward the same social goals.

- Establishing clear lines of authority and responsibility. It is critical to appoint someone who can own the process and make quick business decisions when necessary.

- Recruiting a senior officer to serve as champion for the initiative within the organization.

- Ensuring support from staff and the board as well. Energy and support must come from everyone, not just those directly involved in the social enterprise work.

- Establishing uninterrupted initial cash flow. Social enterprises typically take three to five years to break even.

- Hiring skilled staff. While initially it may make sense to assign responsibility for the social enterprise venture to existing staff, it is likely that you will need to hire new employees to obtain the specialized expertise necessary.

- Tolerating a certain amount of risk. Failure on the road to success is an important source of learning.