Economists are worrying that the recovery post-recession is too sluggish, with only anemic wage growth. One of the culprits, they say, is a slump in the creation of start-up businesses. The Census Bureau reported this month that 414,000 new businesses were formed in 2015, the latest year surveyed—well below the 558,000 enterprises “born” in 2006, the year before the economic decline set in.

“Start-ups…are key drivers of job creation and innovation, and have historically been a ladder into the middle class for less-educated workers and immigrants,” reported The New York Times. “They also play a critical role in making the economy as a whole more productive, as they invent new products and approaches, forcing existing businesses to compete or fall by the wayside.”

Although the start-up slump dates back more than 30 years, economists are most concerned, the newspaper says, about a more recent trend. In the 1980s and 1990s, the entrepreneurial slowdown was concentrated in sectors such as retail, where corner stores and regional brands were being subsumed by national chains. That trend, although often painful for local communities, wasn’t necessarily a drag on productivity more generally. Since about 2000, however, the slowdown has spread to parts of the economy more often associated with high-growth entrepreneurship, including the technology sector.

Second chances and ‘serial careers’

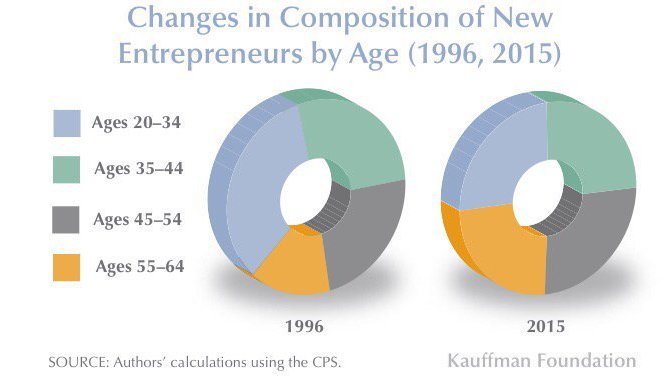

That’s one reason why many members of the NeighborWorks network are working to nurture entrepreneurship in communities across the country, especially among people of color and women—both demographics that traditionally have had less access to the necessary capital. According to the most recent Kaufman Start-Up Activity Index, 56 percent of new entrepreneurs during the average month in 2016 were white, compared to just 24 percent for Latinos, 8 percent for Asians and 9 percent for blacks. Likewise, 61 percent of new entrepreneurs were men compared to 39 percent for women (down from 44 percent in 1996).Among the more encouraging statistics are the significant increases in entrepreneurship among immigrants (who are almost twice as likely as native-born residents to become entrepreneurs) and adults age 55 and older. As the Wall Street Journal reported, “The 55-and-older crowd is now the only age group with a rising labor-force participation rate, even as age discrimination remains a problem for many older job seekers.” More people want to work well beyond what has traditionally been considered retirement age and an increasing number of them are doing so. In fact, as health and life expectancy extend, serial careers—not just jobs—are predicted to be the norm.

Each of those demographic segments has its own unique characteristics, and some NeighborWorks members are tailoring their approach to fit. For example, Maine’s Coastal Enterprises, Inc. (CEI) offers StartSmart for refugees and immigrants, along with its Women’s Business Center. (The nonprofit also offers specialized business consulting to farmers and fishers.)

No matter what the age, sex or race, however, sufficient income is essential to stable housing, a quality education and good health. But more than that, becoming an entrepreneur can be the realization of the “American dream."

“Entrepreneurship is an opportunity for people of all types of backgrounds to gain a level of economic security and control they cannot not find elsewhere,” notes Chanell Scott Contreras, Director of Entrepreneurial Initiatives for ProsperUS Detroit, a program of NeighborWorks member Southwest Solutions. “But it also is a potential route to achieve what for many people is a long-standing dream.”

The problem, of course, is that there are many challenges along the way to starting and sustaining a new business. In fact, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that a bit more than 50 percent of small businesses fail in the first four years. The good news, however, is that with passion, persistence and early education, counseling and technical/financial support, success is possible for most, say network members working in the field.

“Most of the do-or-die problems occur in the first three years,” observes Brian Marshall, Director of Entrepreneurship for BCL of Texas. “The odds of survival start out at 70 percent, but drop to 50-50 over the next 24 months. You’ve got to course-correct early. We’re here to help with that.”

From idea to business plan

One of the biggest and first challenges new entrepreneurs face is defining their product, customer base and “unique value proposition,” says Marshall, who formerly worked for Dell Corp. as an “intrepreneur,” pitching new lines of business internally. He now leads a team of six certified business consultants for BCL, offering classes, personalized coaching and lending.

It can be useful at the very beginning to sort prospective start-up owners into a couple of different categories. One is whether they are wanting to start a new business because they have recently lost a job, gone through a divorce or experienced another life change requiring a different source of income (a “necessity” entrepreneur) or are pursuing a dream (an “opportunity” entrepreneur). Another way to classify them is according to their growth goals: Small business owners, explains Marshall, intend to maintain and expand the operation for their own purposes (perhaps evolving into a legacy for their children). In contrast, entrepreneurs are focused on scaling up to the point when the business can be sold for a profit—and are much more willing to take risks.

Marshall cites a recent example of a nurse practitioner who had been laid off and needed the replacement income (although, fortunately, her husband was employed and supportive). At the same time, she saw the moment as ripe for turning her passion for natural, home beauty treatment into a vocation. (Thus, she is a necessity entrepreneur, with elements of opportunity.) The problem was that she had not precisely defined her offering or her customer base and how to reach them.

“She wasn’t sure about a lot of things,” says Marshall. “For example, should she open her own salon (a service), or was it better to focus on the product and sell to salons or directly to fans at places where they gather? That realization, of the need to define her product, is basic but a real breakthrough for her.”

For this woman, research and market testing was critical. Marshall recommended packaging her banana-and-olive-oil-infused hair treatment, selling it at a farmer’s market for six months and following up with 200-300 customers to solicit their feedback.

“It doesn’t matter if the product is just in a Ziploc bag at that point,” he says. “The question is, is there a market? The only way to know is to get it out there and let people try it. Testing pricing comes later. And then you get the business plan from out of your head onto paper."

Contreras agrees. “We say incubate and start small. [Aspiring entrepreneurs] need to do all the learning they need before they take on substantial loans. It’s easy to idealize what owning your own business is really like, so this is a chance to find out.”

Access to capital

There are four ways to finance a start-up: “Bootstrap” it by investing personal funds; seek money from family, friends and other inner-circle supporters; solicit venture-capital investment; and take out a loan. The latter two are difficult if the individual doesn’t have deep experience in the arena and (for loans) sufficient collateral.

It’s a fact, however, that women have a more difficult time attracting venture capital than men. Jennifer Sporzynski, Senior Program Director for CEI, notes that women entrepreneurs receive only about 4 percent of venture capital. The Harvard Business Review has this to say: “VC firms tend to avoid risk, and therefore, they invest in familiar social networks. Venture capital firms are overwhelmingly male, and men tend to have social networks filled with men. So due to the VC firms’ composition, they tend to fund individuals like themselves.”

Because of this, CEI’s Women’s Business Center has joined a group in Maine focused on recruiting more women into business investing, a longer-term solution to the capital challenge. However, says Sporzynski, the majority of businesses supported by CEI are a better fit for debt financing. CEI helps with that, and much more, through its intensive one-on-one advising, women to women.